Takeaway

The clinically excellent physician knows that sometimes talking isn't enough. When possible, sharing information with patients visually can enhance their understanding.

Connecting with patients | February 5, 2020 | 2 min read

By Rafael Llinas, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

As time goes by, we find that medicine has changed. Not necessarily for the reasons people think. The practice has evolved, not because of documentation, or billing, or medicolegal responsibility, but with the changing relationships with our patients.

Gone are the “Marcus Welby, MD” days where physicians made pronouncements and patients complied with treatments, if those days ever truly existed. Nowadays patients are both better and more poorly informed. In the past, it was rare that a patient knew anything about their uncommon disorder Now with a click of a button Google will tell patients everything regarding what they have or what they think they may have. This can be a blessing, though many physicians think of it as a curse as it can cause patients to doubt that the diagnosis or treatment is correct.

People have been given cause to doubt everything we are told by those in authority. The Vietnam War started because they shot first, or not? Kennedy was a great president, or not? Oil price hikes are due to Saudi price gouging, or not? America went to war over weapons of mass destruction that were absolutely there, or not? More unfortunate is the growing doubt about global warming, as well as the safety of vaccinations.

In this context, one can better understand when a patient is suspicious regarding the diagnosis of stroke when they have improved, or the diagnosis of brain death in a loved one. What is the solution? Our experience as educators can sometimes help. The same tone and explanation techniques can be used in talking to patients as with medical students and residents. Summarize the symptoms and physical exam findings, discuss a short and relevant differential diagnosis, then explain why certain diagnoses are not present or what you plan to do to rule in or out the disease. Make the patients part of the thought process. If they bring up an alternative diagnosis, how would you address if they were a student? “Great thought but I don’t think that’s it because of ….” What patients cannot get from the internet is this reasonable, intelligent, and personal discussion.

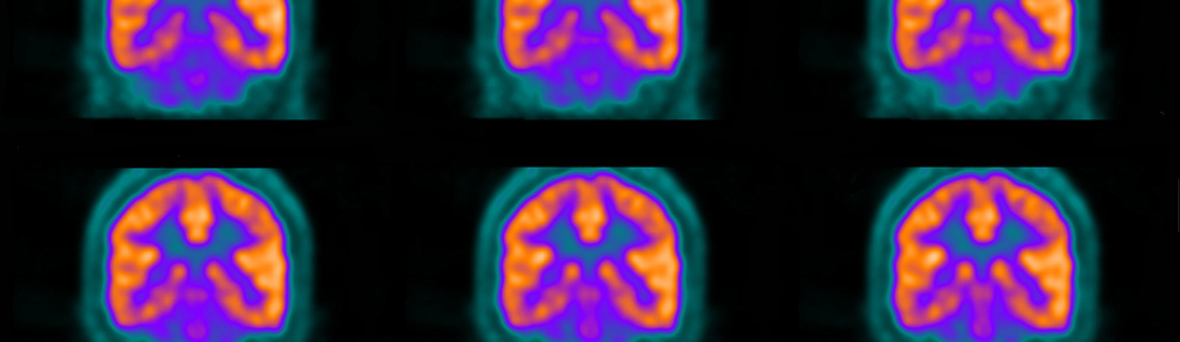

There are times when talking isn’t enough and “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Show them the scan. Show them the chest x-ray, the CT scan, the PET scans, the ultrasound, and the lab tests. These days it’s so easy to pull them up. Make a point of confirming it’s their image and that the date is recent. Show them the abnormality or lack of abnormalities. Show them the data you used to make your decision.

In my practice showing a patient a normal MRI scan when they are convinced that they have a particular diagnosis (after showing them Google images of typical MRI findings for that disease) goes a long way. Showing patients their imaging when an incidental finding is noted is very useful, as is a head CT showing a devastated cerebral cortex, or hemorrhage when discussing end of life issues with a family.

Patients, like most people, believe what they see. Teach patients how to think about the problem, and then show them the data.