Takeaway

Bolded, flagged, or typed in a different color, an abnormal result demands the mind’s eye in many modern EMRs, but it is equally important to direct our gaze to the quietly normal labs; not uncommonly, they may be screaming a powerful clue.

Lifelong Learning in Clinical Excellence | June 3, 2019 | 1 min read

By Rabih Geha, MD, University of California San Francisco

On episode 34 of the Clinical Problem Solvers, Dr. Sharmin Shekarchian presented a fascinating Human Diagnosis Project case to Drs. Stephenie Le, Harry Han, and myself.

Description

A clinical syndrome characterized by subacute disequilibrium, nausea, and dysmetria landed us in the cerebellum. With clarity in the foreground (cerebellar pathology), we were tasked with understanding how the patient’s background would inform the differential diagnosis.

The patient had a known BRCA mutation with two known prior cancers – breast and ovarian. Naturally, this information took center stage.

The main question

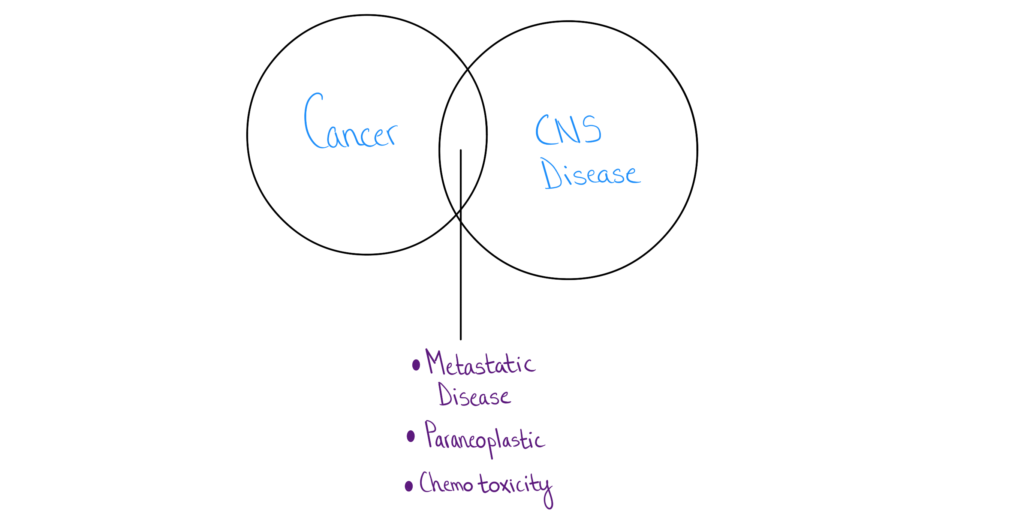

From a diagnostic perspective, the question was: how can a patient with malignancy develop cerebellar pathology?

Or, more loosely, what are the ways cancer leads to intracranial problems?

If this intracranial problem was in fact related to the patient’s known malignancy, we were confident that it would boil down to one of three things: metastatic cancer, paraneoplastic disease, or a side-effect of prior treatment (e.g, chemotherapy toxicity).

“Normal labs”

When the renal panel and liver enzymes came back normal, our initial inclination was: “I don’t think these normal labs change our impression much.” My mind finds it much harder to attach diagnostic significance to pertinent negatives. Even if their impact on a diagnostic hypothesis is equal, I find that a positive test result sways my reasoning more so than an equally impactful negative test.

Taking a simplistic approach, before the labs come back, there are two outcomes: this intracranial process has some systemic involvement (kidney and/or liver dysfunction), or the problem is exclusively in the brain.

Had the labs come back positive, our suspicion for metastatic disease probably would have risen, and so normal labs have to swing our diagnostic needle away from metastatic disease and to paraneoplastic process.

There are, of course, several cancers that metastasize to the brain alone, and so the diagnostic needle may not swing much, but it certainly nudges toward a paraneoplastic process, especially when compared to the alternate scenario of “positive” labs.

Mind’s eye

Bolded, flagged, or typed in a different color, an abnormal result demands the mind’s eye in many modern EMRs, but it is equally important to direct our gaze to the quietly normal labs; not uncommonly, they may be screaming a powerful clue.