Takeaway

Visual Thinking Strategies and the Personal Response Tour are two examples of museum-based pedagogical practice that build critical thinking skills, foster empathy, and allow for reflective space away from the clinic.

This is the third in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients).

Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in March.

Dr. Chisolm:

This month I traveled to Boston for a course at the Museum of Fine Arts in Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), a teaching method in which I am seeking certification. VTS fosters learning in the domains of critical thinking, communication/collaboration, visual literacy, and mindset by encouraging learners to make observations, reason with evidence, speculate, evaluate, and revise ideas. VTS increases empathy and respect for the views of others, provides the skills needed to analyze and find meaning in works of art, and nurtures intellectual curiosity and openness to the unfamiliar. After two days of looking and talking about art, you would have thought I had had my fill; but while wandering the galleries as a group, one particular painting had repeatedly caught my eye. After the course ended, I decided to spend one last evening in the museum to look more closely at this painting.

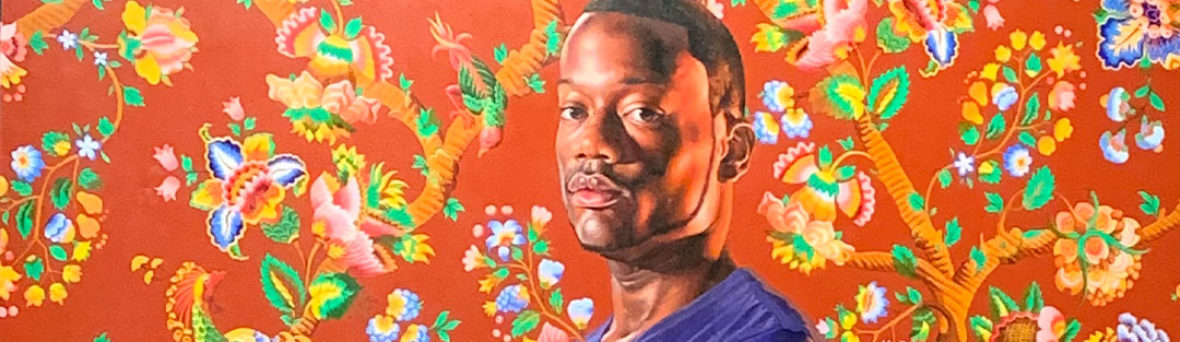

The painting is large. Framed, it is a little shy of 7 feet tall and 6 feet wide. The painting is colorful: vibrant pink, red, yellow, green, and blue flowers, vines, and tendrils curl across a field of deeper red. This decorative floral pattern, evocative of a William Morris wallpaper, only serves as the background against which the central figure of the portrait stands; a figure who commands our attention and who draws us in. It is to look at him that I return.

Although posed using the conventions of historical portraits, like those by John Singer Sargent, this figure is clearly not from that era. This figure is dressed in modern street clothes (a bright blue Express tee shirt and form-fitting dark blue jeans). And he is a black man, someone who would never have been the subject of such a portrait at the time. Yet here he is, looking down upon us with a bold gaze and an air of confidence befitting a nobleman. Flowering vines emerge from the wallpaper to encircle gently the subject’s fit torso and muscular arms and legs. These daisy chains are not going to hold this noble man back. They cannot hold him down. His body exudes strength. His eyes meet mine and say, “See me. Hear me. Look up to me.”

What does this painting, “John, 1st Baron Bryon,” by Kehinde Wiley (whom Obama selected to paint his official Presidential portrait) have to do with clinical excellence? Well, I think a lot.

This portrait reminds me of the inherent dignity of each of our patients, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, or socioeconomic status. Each patient we encounter is someone worthy of our respect. We need to see each of them as the noble person they are, to listen to them, and to look up to them. And we need to serve them.

Dr. Smyth Zahra:

This month, I had the pleasure of welcoming our codirector from the Harvard Macy Art Museum-based Fellowship, pediatrician Dr. Lisa Wong to King’s College. Lisa, who is also a codirector of the Arts and Humanities Initiative at Harvard Medical School, brought along one of her students. It therefore seemed appropriate to introduce our guests to some of the Clinical Humanities dental and medical students, and for me to put into practice recent learning from our January session in Boston.

London Personal Response Tour

We met at the East Wing of Somerset House, part of Strand campus, and embarked on a “London Personal Responses” walking tour. “The Personal Response to Art” was conceived by another of our fellowship codirectors, Ray Williams, from the Blanton Museum of Art at The University of Texas, and has been successfully implemented at Harvard Medical School by our fellowship founder, director Dr. Elizabeth Gaufberg.

The personal response tour invites participants to spend time in an art museum and via a written prompt to seek out a piece of art that resonates with them, and then share their findings with their group. The focus is not art appreciation expertise or observation skills, but rather, on interpretation, personal reflection, and dialogue away from the usual clinical spaces. I had arranged to take the group a short walk away to the John Ruskin exhibition at Two Temple Place that I mentioned in the first blog post. There, we each shared our responses to a piece of art and found in that time how much we learned from each other with space for collective reflection on the interpretive nature of clinical care and the students’ professional identity formation.

We then carried on over London Bridge, through Borough Market to Southwark Cathedral. After sharing our mutual connections to John Harvard, “the godly gentleman and lover of learning,” in the Harvard chapel, it seemed particularly apt on the same day as over one million people were marching on Westminster to demand a people’s vote, to spend time with Sarah Christie’s “Library 2016-2019” installation. The ancient Greeks voted by writing on ostraca (pot sherds). At the time of the EU Referendum in 2016, Sarah invited the public to write on ceramic sherds from 150 cast bowls and the collection of 2,000 pieces may currently be seen on the altar steps of the chapel of St Francis of Assisi and St Elizabeth of Hungary. The collective words form a complex text and are a permanent record of a particular moment in time. For me, this powerfully emotive artwork is both a literal and metaphorical representation of complexity in uncertain times exhibiting both the fragility and strength of our collective humanity.

We ended our tour back at the Science Gallery on our Guy’s campus. Our London version of the Personal Response Tour was a fantastic opportunity for collective reflection and interprofessional conversations. Art-as-prompt scaffolded students’ interpretive skills and captured nuanced thinking on the ambiguous nature of much of their burgeoning clinical experience.

Outside the Science Gallery at King’s College’s Guy’s campus, London, engaged in our own version of the Personal Response Tour.

Stay tuned to CLOSLER for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in April.