Takeaway

Clinicians must counsel their patients about the dangers of firearms. If they decide to be gun owners, advise how to store them safely.

| January 22, 2019 | 4 min read

By Cassandra Crifasi, PhD, MPH, Katherine Hoops, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

Providing guidance on a range of relevant topics is a core clinical competency for all healthcare providers. Physicians counsel their patients on a host of health risk behaviors every day, from car seats for children, to falls in elderly adults. Validated models exist for counseling on certain behaviors and conditions associated with major health risk reduction, including smoking cessation and weight loss.

Implementation of the 5A’s model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) has been shown to improve motivation to quit and increase quit attempts among smokers, as well as increasing motivation to lose weight, certain diet change behaviors, and actual weight loss among obese patients. Given that, in 2017, nearly 40,000 people died from firearm-related injuries, this validated model should be applied to firearm safety counseling.

First, physicians can and should counsel patients on gun safety. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) prohibits required collection of firearm information but does not regulate communication between physicians and patients with regard to firearms. After the Florida Privacy of Firearm Owners Act was overturned as a violation of physicians’ First Amendment rights, no state statute exists that restricts physicians’ ability to discuss firearm safety with patients.

Safe storage practices are effective in reducing firearm injuries, and physicians can motivate patients and families to store guns safely. However, while most pediatricians believe that they have a “responsibility to counsel families about firearms,” prior research found that only about 20% of pediatricians asked more than 5% of their patients about gun ownership. A recent nationally representative survey of U.S. gun owners revealed that less than 20% rated physicians as effective messengers about safe storage practices. These findings suggest a need for additional research to explore the role of physicians in providing anticipatory guidance on safe gun storage. We propose an extrapolation of the 5 A’s model as a guide to firearm injury prevention counseling for clinicians.

Ask

Every patient needs to be asked about the presence of guns in the home:

1.) Are there guns in your home?

2.) What type of guns are in your home?

3.) Who do the guns belong to?

4.) How are the guns stored?

5.) How is the ammunition stored?

Advise

Advise your patient in clear and personalized language on the potential risks of guns in the home. A large body of evidence demonstrates that the presence of firearms in the home is associated with increased likelihood of suicide, homicide, and unintentional injuries. Safe storage practices including keeping firearms stored unloaded, locked, separate from ammunition, and/or with an extrinsic safety device are protective against unintentional injuries and suicide attempts.

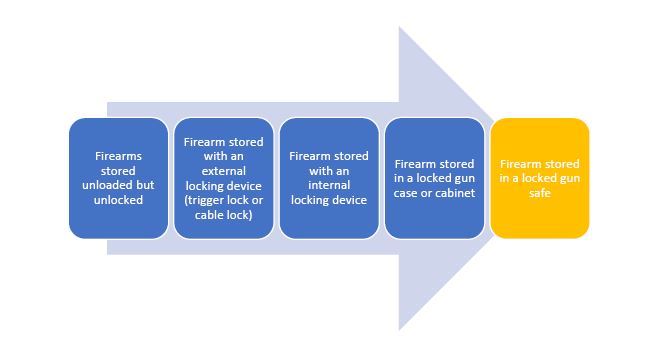

All firearms should be stored unloaded and separate from ammunition. There is a spectrum of options for storage which offer increasing degrees of safety.

As an alternative, firearms may be stored safely at a local gun range or club.

A firearm that is stored loaded is not safely stored, even if the gun owner thinks that the gun is in a location that is inaccessible to children or at-risk adults. While removing guns from the home entirely is not feasible for some gun owners, we recommend removing guns from the home when there is concern for depression, suicide, or interpersonal violence, especially when the person at risk is an adolescent or elderly person with dementia.

Assess

Assess your patient’s interest in implementing safe storage practices or removing guns from the home.

If patients are not interested, try to determine the barriers to safe storage. For example, if patients are concerned about their ability to access a firearm quickly, you can advise them that there are safe storage devices that still allow for quick access and use by authorized adults. If patients feel that the risks of unsafely stored firearms are irrelevant in their home, you can advise them that even if there are no at-risk individuals in a home, safe storage reduces the likelihood of gun theft, an important source of guns used to commit crimes.

You can say, “How can I help you store your guns safely?”

Assist

For patients interested in making a change, provide them with resources that facilitate the behavior change. Gun safes come in a range of sizes and styles based on storage needs and financial resources. Trigger locks and cable locks can be found at many retailers often for under $10. In one recent survey, less than 10% of practices actually provide firearm locking devices to their patients. With many low cost options available, this is an opportunity to assist low income patients to store guns safely.

Contact your local police station regarding gun surrender or gun buyback programs.

Arrange

Follow up with your patient in one – two weeks by phone or in person to see if they have been successful in obtaining and using a safe storage device. If not, provide further assistance. Positively reinforce positive behavior change.

There is an urgent need for further research on physicians as messengers on firearm safety. However, this need for research should not dissuade clinicians from counseling their patients in a way that is well-informed and culturally competent: asking patients about firearms and providing patients with advice on safe storage and assistance finding local resources.