Takeaway

My preceptor’s office contained artistic depictions that at first, I found disturbing. After observing his trusting patient-provider interactions, I was able to appreciate hope and fragility both in patient stories and in art.

Passion in the medical profession | December 17, 2025 | 2 min read

By Ted Chor, pre-medical student, Johns Hopkins University

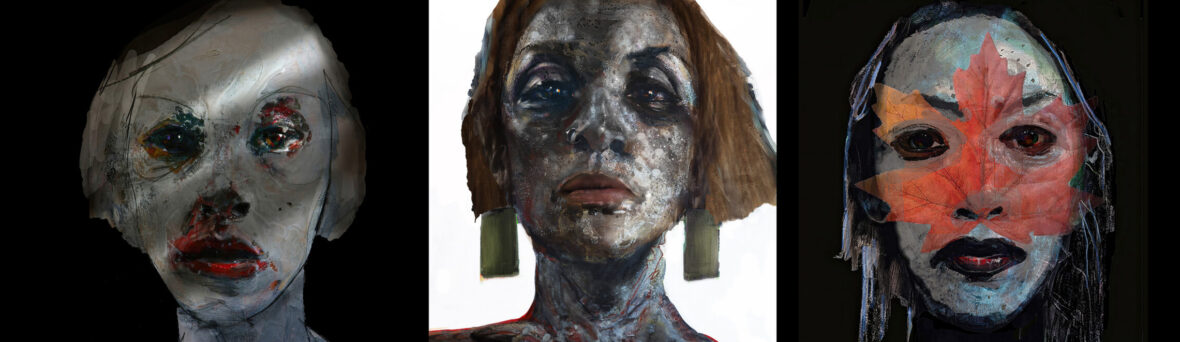

When I got off the elevator, I was greeted by art pieces about the size of doors lining the hallway. As I walked past the paintings, I became increasingly unsettled—the paintings were macabre portraits of individuals set against shadows that threatened to swallow them whole. Their eyes, shining like scattered reflections of the moon on dark water, haunted me. I couldn’t quite place what was within their depths—was it pleading? Silently, they watched me through the hallway, the waiting room, and the clinic. Some had splashes of red, pink, or blue, reminding me of a fading sunset and encroaching nightfall.

I then saw eight patients with the addiction medicine physician I was shadowing. Though if I’d only heard the conversations and not the setting, I would have said I saw Dr. Fingerhood catch up with eight friends. One patient brought him a magazine of Rod Stewart’s model train collection. Another showed off a jacket he’d won from a pigeon race. Another had recently lost a job, and Dr. Fingerhood commiserated with him. Yet another bemoaned the trading of various players from the Ravens.

At first, I was awed by his immense literacy in every single subject that patients talked about. But then I realized his literacy wasn’t in his patients’ interests—it was in their lives. Trust and laughter flowed freely between Dr. Fingerhood and his patients—an overflow of a relational abundance cultivated over decades. The knowledge of his patients’ lives was matched equally by his care and devotion to their flourishing.

My own apprehension toward primary care dissolved as I partook in the richness of relationships from one visit to the next. Most of the patients we saw that morning had overcome a substance use disorder and were testimonies of triumph and resilience. Graciously, Dr. Fingerhood invited patients to share tidbits of their stories with me.

As they spoke, I thought about things I’d hard patients say about Dr. Fingerhood. “I felt like this man was gonna give up on me, but he never did, and that meant the world to me.” Another said, “He was one of the first to touch me, because those days you were barely touched.” And another shared, “I looked to Dr. Fingerhood like he was another father, because I felt like . . . I could confide in him.”

When I left the clinic, I saw the paintings differently. Perhaps the characters represented a resistance to darkness rather than dissolution into it. I saw resilience, toe-to-toe with despair. And the light in their eyes, maybe it was the flicker of hope, fragile, but not fleeting.

This piece expresses the views solely of the author. It does not necessarily represent the views of any organization, including Johns Hopkins Medicine.