Takeaway

Opportunities to ease distress extend beyond the bedside and outside of the clinic to every interaction with our patients and also their caregivers.

Passion in the Medical Profession | November 15, 2018 | 3 min read

By Ishwaria Subbiah, MD, MS, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

It was my turn to round that weekend on our palliative care team’s inpatient consult service. The coffee line in the hospital cafe was unexpectedly long for a Saturday morning at 6:30 a.m. The lone barista didn’t anticipate 11 people at the same time before sunrise.

A surprising question

After we hit the three-minute mark, most of us were done fiddling with our phones. We looked up and smiled politely at others in the line – we were the standard mix of families, caregivers, nurses, physicians, other providers, and staff. The man in front of me turned around and glanced at my name and department embroidered on my white coat with a puzzled look. I assumed he was attempting to decipher the pronunciation of “Ishwaria Subbiah,” but instead, I was pleasantly surprised when he asked, “What is palliative care?”

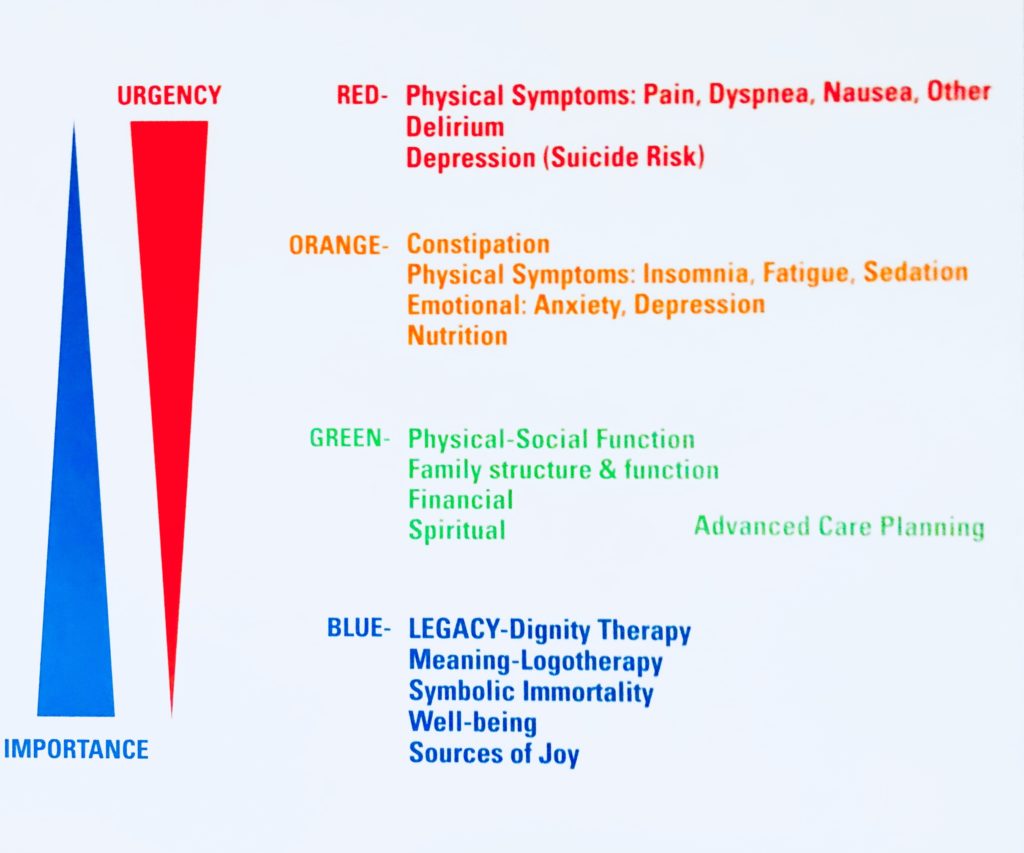

I work in a cancer center where I first began as a fellow in Medical Oncology, cultivating a clinical practice with a multidisciplinary team that emphasizes addressing the distress of the whole person, be it physical symptoms including cancer pain, shortness of breath, or nausea, to those with perhaps a deeper importance such as legacy planning and spiritual well-being, illustrated in the figure below:

Since I practice a in field that revolves around matters of personhood in an institution powered by advances in precision medicine and novel therapeutics, I have enthusiastically answered many questions about palliative care – this inquisitive person in the coffee line was no different. With his furrowed brow and peering eyes, he took a step towards me perhaps hoping closer inspection would provide further clarity. He appeared to be in his mid-40s, with a tiredness in his voice likely from being awake for the better part of the previous night – however, in his weary voice and smile, there was a genuine interest in what I do.

“Well, palliative care is whole-person care,” I began, watching his brow furrow even deeper. I shared about the origins of my field as one born out of the critical need to mitigate suffering at the end of life. Over the decades, palliative care in cancer has evolved to become comprehensive symptom management for persons from the moment of diagnosis and as they receive cancer treatment, rather than exclusively end-of-life care, which still remains an important and valued part of my practice.

The next 12 minutes flew by. We discussed the nature of a typical palliative care encounter and we reviewed the members of the multidisciplinary team and their respective roles in the global mission to provide holistic care. He asked questions and I answered, but I hesitated to reciprocate with inquiries about him and his role here – after all we were standing in line the coffee shop. Was he here as a husband, a friend, extended family of a patient? I waited for him to volunteer this information but it was not to be. With his furrowed brow now resolved and a sense of calm in his demeanor, he replied, “Thank you for speaking with me and for explaining what you do,” and we parted ways.

A meaningful page

I received a page three days later from a medical oncology team: “Hello Dr. Subbiah. Patient S is not doing well and the patient’s son met you in the coffee shop just a few days ago. The family really wanted to see you and was asking if you can please come by and talk to them. Thank you.”

The moment of conversation in the coffee line evolved into a valued relationship between our palliative care team and that family over the next two weeks. Faced with advancing illness and profound grief, our profession immediately addressed the higher acuity symptoms causing overt distress with robust, data-driven interventions while concurrently aiding the patient and family with decision-making and planning that were in line with the patient’s values and wishes. We had conversations with immediate and extended family on what to expect, significantly mitigating their fear of suffering towards the end of life, and ensuring that the patient would have “a good death.”

Opportunities to ease distress extend beyond the bedside, outside of the clinic or inpatient room, and in every interaction with not only the patient, but also their caregivers. However, that aid can only be provided with our acknowledgment and conscious recognition that manifestations of distress transcend overtly perceptible physical symptoms. Distress permeates however subconsciously into every aspect of the healthcare experience, even and especially in the coffee line.