Takeaway

Slow looking can enable clinicians to see more deeply, think more critically, and engage more meaningfully in patient care. Time spent in a museum supports clinician wellness and nurtures student professional identity formation.

This is the fourth in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients). Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in April.

Dr. Smyth Zahra

Previous work has shown that most people spend between ten to thirty seconds looking at a piece of art in the museum space. Some will capture the significance of that moment in time on their camera, connecting self and other via their close proximity to the work. For many, the art is incidental, a subservient backdrop to the narcissistic portrayal of self on a public facing Instagram timeline. As an antidote to the problem that, “Many people don’t know how to look at and love art and are disconnected from it,” Phil Terry founded The Slow Art Day movement which took place in many art galleries around the world this year on April 6.

Slow Art has been likened to “sacred looking, wanting people to see more and engage more deeply” by the event-lead at the Natural History Museum, London, who recalls “when the Natural History Museum was built and founded it was called a cathedral to nature and people used to come in and take their hats off in awe.”

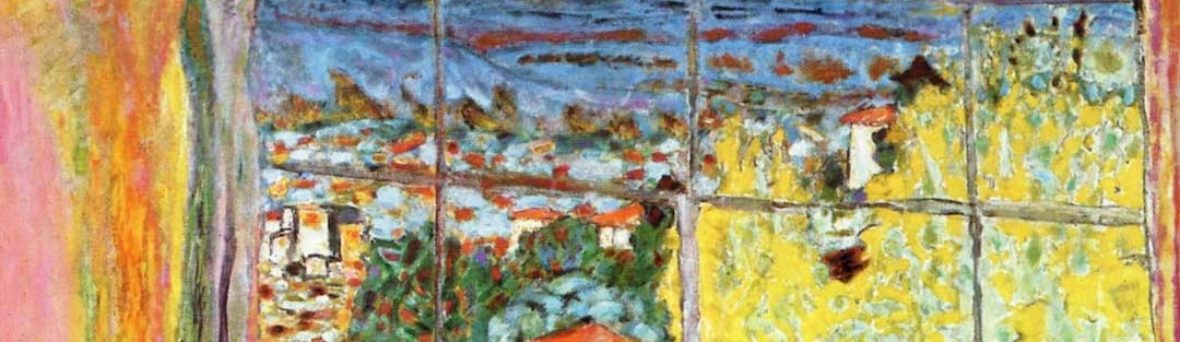

I spent over an hour in Tate Modern looking at just one painting, “L’atelier au Mimosa” (1939-46). Bonnard is famous for capturing a glimpse, a moment in time, which he painted from memory, always with amazing use of colour. The sheer vibrancy of the golden mimosa draws the eye outwards, through the window; looking long enough, one starts to see the breeze moving the blossom and smell the scent. It takes much longer to return one’s gaze inwards to the pink and orange tones, to appreciate the interplay of interior and exterior, self and other, personal and public. I was dwelling on this use of colour and Bonnard’s faceted, layered approach, reflecting that the ability to comfortably hold multi-perspectives, philosophies of self and other, what we choose to portray to the world, are all linked to professional identity formation, our ability to learn, and “ways of being” a clinician. It was only when I was about to leave, that I became aware of the figure in the lower lefthand corner of the painting. I couldn’t believe that I had been so intently engaged for over an hour yet had missed this ambiguous form, with eyes, open or closed, and the ethereal presence imbued the painting with a sense of melancholy only heightened by the bright colours.

Later, I read that Bonnard’s muse was his wife Marthe, who had lived for many years with illness, and many of his paintings capture glimpses of her at their home. She was ever present, he cared for her for many years, but by the time he painted “L’atelier au Mimosa,” she was already dead. Maybe she was still present in his memories? There is a bitter sweetness in the work and the time I spent looking closely, getting to know what I could, from what I was able to observe and what the artist chose to portray, in many respects felt like a clinical encounter. I left with an overall pervading sense of compassion for the man, his memories of the woman he loved, and his work.

Shari Tishman, Harvard lecturer, advocates experiential learning in museum spaces and deliberate, mindful close observation as an epistemic virtue in her 2018 book, “Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation.”

Certainly, the AMHPE fellowship has afforded me time to closely observe, reflect, and to explore both alone and collectively. Together, we AMPHPE Fellows have experienced and been role modelling the close observation, critical analysis, transformational learning, and “the ways of being” we are trying to nurture in our clinical students’ own professional identity development.

Dr. Chisolm

In April, I found myself back in Fort Worth, Texas, for another research grant meeting, and decided to return to the Kimbell Art Museum. When I had visited the Kimbell last September, I spent the entire day looking at every piece in the collection. This time, inspired by Dr. Smith Zahra’s embrace of Slow Art Day and Shari Tishman’s excellent book, “Slow Looking,” I decided to spend my entire visit looking closely at one piece of art. I selected “The Cardsharps,” painted by Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi) in 1595.

‘Genre paintings’ depict a scene from everyday life, and sometimes include a moral theme. As preparation for the art-museum based elective in human flourishing for fourth year medical students that I’m developing in the AMHPE Fellowship, I’ve been reading “Lost Virtue: Professional Character Development in Medical Education,”and was looking for a painting that specifically included themes of character and virtues. I also wanted to choose a painting whose narrative would be readily accessible by medical learners. ‘The Cardsharps’ fit the bill perfectly.

The three figures dominate the painting, engrossed in a game of cards. The light draws our gaze to the figure at the far left who appears wealthier and less world-weary, more innocent, than the other two figures who – despite their age difference – are linked together by their striped clothing in an act of conspiracy. Slow looking gave me time to consider the colors, shapes, and lines of each figure’s clothing. I was able to notice the patterns of the game board, the numbers on each die, the hint of facial hair of the figure on the far right, the texture of the feathers in his cap, the emotion in his eyes, the tension in his left hand, the numbers and suit of the cards in his left. I had time to consider the juxtaposition of the figure on the far left with the other two figures. And the juxtaposition of the Caravaggio painting with its neighbour, “The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs,” by Georges de la Tour, that explores a similar theme.

I bought a printed reproduction of the Caravaggio back with me to share with my inpatient team of two psychiatry interns and two medical students. After our first morning rounding on patients together, we took a Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) break to spend 15 minutes looking at “Cardsharps” and engaging in an authentic group discussion. By doing this, I wanted to demonstrate the qualities of a supportive learning environment, one that is open and accepting, encourages risk-taking, and strives to elicit multiple perspectives.

We first took a silent moment to look at the painting. I then asked, “What’s going on in this picture?” and paraphrased each response and, when applicable followed up with, “What do you see that makes you say…?” and a paraphrase of each response. After a learner offered his/her thoughts, I then asked, “What more can we find?” to elicit other’s observations and reflections. At the end of the 15 minutes, after all four learner had participated, I thanked for their time and openness. Surprisingly, none expressed any curiosity about the painting itself: its origin, title, date, nor the artist’s intent.

The first goal of VTS is to develop critical thinking as the learners hone their ability to make observations, reason with evidence, speculate, evaluate, and revise ideas. In medicine, we call these clinical reasoning skills and they are a pillar of clinical excellence. Even after one brief session with “The Cardsharps,” the learners showed improvement in these skills. In fact, by the end of the fifteen minutes, the learners’ thoughts about who was duping whom had reversed completely, in fact.

The next goal of VTS is to encourage communication and collaboration via strengthening speaking and listening skills, giving learners confidence in and ability to express themselves, increasing empathy and respect for the views of others, and valuing multiple perspectives. Again, all of these skills are essential to connecting with patients, and are another pillar of clinical excellence.

In our session with “The Cardsharps,” the learners clearly valued and built on one another’s unique points of view. The third goal of VTS is to improve visual literacy by increasing ability to analyze and find meaning in works of art and to develop a personal connection to art. Although this skill is less clearly relevant to clinical excellence, being able to enjoy looking at works of beauty is restorative and an act of self-care, which can allow a clinician’s passion for the medical profession to continue to thrive.

The fourth and final goal of VTS is to develop one’s mindset by nurturing intellectual curiosity, perseverance, and openness to the unfamiliar, all of which are fundamental to lifelong learning in clinical excellence. CLOSLER honors the values of William Osler, who revolutionized formal medical education by teaching at the bedside. Bringing the arts and humanities to clinical teaching will help us be more clinically excellent and so get us all a little Closer to Osler.

Stay tuned to CLOSLER for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in May.