Takeaway

The more lessons on clinical excellence we look for in art, the more we find.

This is the second in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients).

Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in February.

Dr. Smyth Zahra

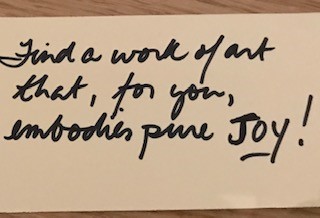

As part of our January session of the Harvard Macy Fellowship, we participated in a Personal Responses Tour at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, as designed by two of our co-directors Dr. Liz Gaufberg and Mr. Ray Williams. I was charged to find a work of art that embodied ‘pure joy,’ and sure enough the more joy I looked for in that beautiful gallery space, the more joy I found!

Returning to King’s College London:

Returning to King’s College London from such deep immersion in the museum space to my role as a dental educator, February has been full of art related activities with my faculty.

It seems the more art I look for, the more I find. I have been extolling the virtues of embedding arts and humanities approaches and epistemologies into clinical curricula for some time now, dating back to my first Clinical Humanities pilot in 2015:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgqLS50NqSA&feature=youtu.be

Transdisciplinary collaborations

This past year has also seen a new venture, as part of King’s Cultural Innovation program, we partnered some of our faculty research scientists with artists in order to explore transdisciplinary collaborations that might enhance understanding of oral disease and improve patient care. In February, we showcased some of the outputs of this experimental arts-based approach to scientific research. The setting of the East Wing of Somerset House on our Strand Campus seemed particularly appropriate, since it was here that both the Royal Academy of Arts and The Royal Society had their home from 1779 – 1836, at which time they moved to their present location at Burlington House Piccadilly. Here are details of the various collaborations.

Xerostomia

The various research and art collaborations are all very different, but certainly the ability of art to reveal multiple truths juxtaposed and reinterpreted by clinical, basic, and translational research scientists, proved very powerful and illuminating. Making the intangible visible, the beauty of the salivary gland was exhibited in the form of 3D printed models and in photographic interpretations by the artist Emma Barnard @PatientasPaper, patients’ voices were evoked making explicit the disability of living with xerostomia. The below image of salt pouring onto a model of the salivary gland is both emotive and disturbing. I cannot think of a better way of teaching students about the effects of xerostomia and what it actually feels like to live with this oft cited “hidden disability.”

Back at our campus, we now have our own art gallery, and in February we opened a new exhibition, “Spare Parts,”featuring the work of another one of our faculty researchers, Professor Lucy di Silvio and artist Burton Nitta drawing attention to the debate in Britain surrounding tissue engineering from an artificial voice generated bioengineered vocal box.

Our working space defines us. Surrounded by the clinical, and now with so much art co-created by our very own researchers working alongside fantastic creatives, we can increase understanding of oral and systemic disease. Encouraging cross paradigmatic thinking and collaboration can only help our researchers be more creative, and innovate to improve patient care. It is culture that supports cell growth, but also culture that nurtures us all.

Dr. Chisolm

I had the good fortune to travel to Hawaii for the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists. Another AMHPE fellow, Dr. Mary Blazek, recommended I visit the Honolulu Museum of Art. The Honolulu Museum of Art’s collection includes European/American art from antiquity through the 20th century, but the Museum’s collection of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art is most remarkable, considered one of the most important of any American museum.

Guanyin

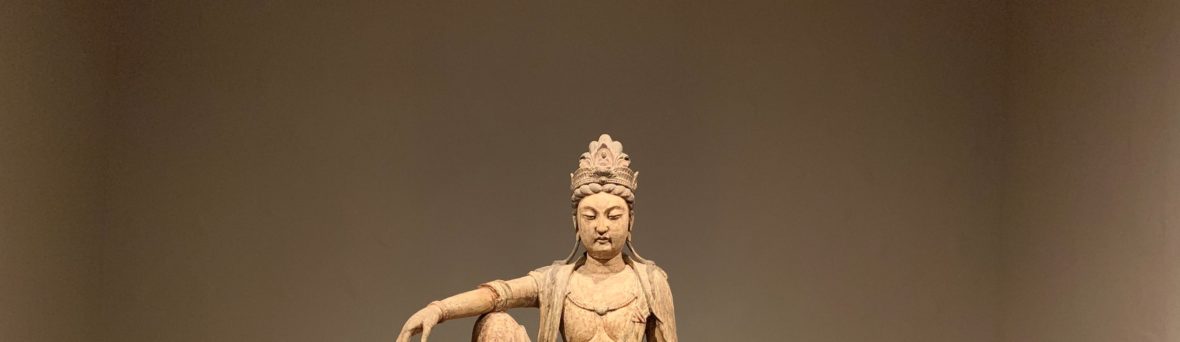

As I wandered through all of the Museum’s galleries, many objects caught my eye, but none was as compelling as the large wooden sculpture of Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion. I spent over a half hour in contemplation of this figure, knowing only his name, ‘age’ (11th century), and nationality (Chinese).

This is what I saw:

A larger than life male figure, sitting on a raised wooden platform who asks me to look at him from below. He is sitting in a strikingly relaxed and open pose, suggestive of an embrace. He extends his right arm, palm down, resting it on his bent right knee. Yet he is solid. His left leg rests firmly on the ground, with his right arm bent, suspended in the air, with his palm facing upward. His right hand’s fingers are long, relaxed, and slightly curled. The middle finger of his right hand is touching his left thumb, forming a circle. But it is his face that draws me in closer.

This is what I thought and felt:

His eyes seem intentionally to not meet mine, out of respect for what I am feeling. His eyes are downcast. He looks almost half-asleep when viewed from beneath, dreamlike. His half-smile evokes a sense of kindness and warmth. His face expresses intimacy, knowingness, love, forgiveness, mercy, and – more than anything – patience. He looks like he has all the time in the world for me. Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion. This is what our patients want from us.

This is what I learned later:

This is, indeed, a large figure. Seated, the sculpture measures five feet, seven inches. His Chinese name is Guanyin, short for Guanshiyin, which means “[the one who] perceives the sounds of the world” (i.e., the cries of beings who need his help). All representations of the Bodhisattva in China prior to the Song dynasty (960–1279) were masculine in appearance.

In modern times, however, Guanyin is more often depicted as a woman and some people believe that Guanyin is androgynous or perhaps without gender. Guanyin has also been compared to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Like Mary and Guanyin, may all of us clinicians hear the cries of all who need our help and respond with patience and compassion.

Stay tuned for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in March …