Takeaway

Learning how to work with patients on ventilators at home has been a gratifying challenge.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | June 21, 2018 | 6 min read

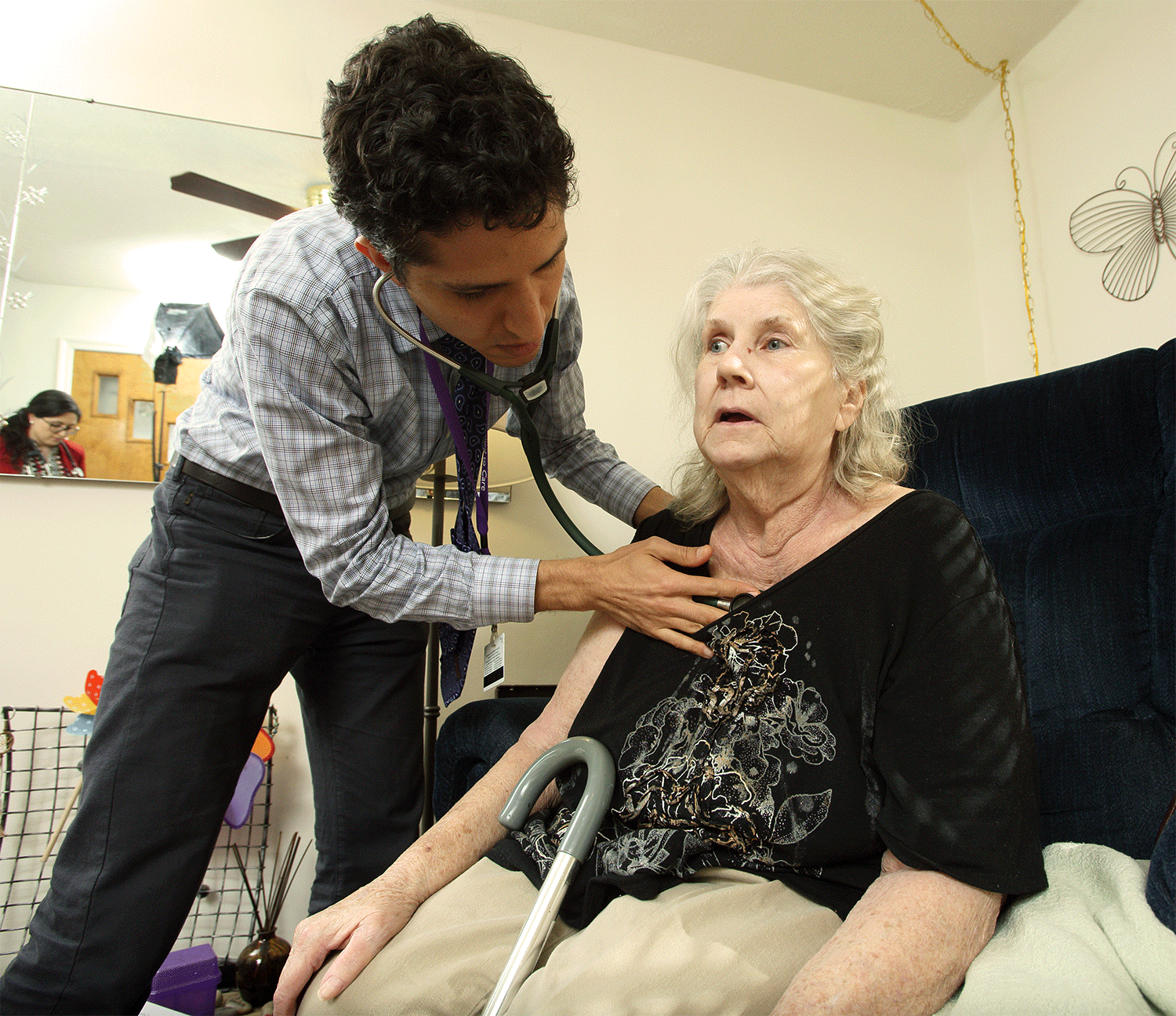

By Mattan Schuchman, MD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Learning how to work with patients on ventilators at home has been a gratifying challenge. Taking care of a patient at home with a ventilator meant refreshing old skills about managing ventilators and learning new ones like how to troubleshoot the ventilator at home. Managing a home ventilator can be a challenge for patients and caregivers. Because it can be so difficult to physically get to see a doctor for a patient on a ventilator, a home-based medicine program like Johns Hopkins Home-Based Medicine is a perfect fit.

Some patients who are discharged from the hospital and aren’t able to be taken off the ventilator are then faced with the prospect of remaining in a facility – unless the have adequate supports, such as dedicated caregivers or family members who can learn to manage a ventilator and provide 24-hour care.

While it’s common in European countries for people who require ventilator support to live at home, it’s relatively rare in the United States. The necessary infrastructure, such as training programs for family members, home-based medicine programs, and affordable care for hire in the community, isn’t common in America, but hopefully will become more available in the future.

Creating this infrastructure will, in the long run, save costs by reducing reliance on nursing homes, provide higher quality care that is aligned with patient preferences (most people would choose to return to their homes if given the option), and will likely provide better health outcomes (as shown in international studies and research underway by Dr. Greenough and colleagues). In the last two years working for Johns Hopkins Home-Based Medicine (JHOME) I’ve taken care of five such patients and I learned new lessons from each one.

Ms. G

Ms. G was the first patient I cared for that was dependent on a ventilator who had been discharged from Dr. Greenough’s unit. I was frightened on my first visit that I wouldn’t know what to do. I was familiar with the vent mechanism and the basic mechanics of ventilator breathing from my time working in the ICU as a resident, but it had been about two years since then.

What if I couldn’t remember the difference between the different vent settings that all go by acronyms like AC and SIMV? What if something was going wrong and I needed to troubleshoot the vent? How do I know if we’re ventilating properly without access to blood gas analysis? You would like me to do the tracheostomy tube change? Excuse me?

As I would learn here and again later on, patients have been my greatest teachers. Ms. G taught me that I could work with her and learn together with her the ins and outs of care on the ventilator. Her little terrier would jump up on her bed and lick my hands when I would visit, but even germs from that little rascal are better than the kinds of things she would have encountered in the hospital. One of our great triumphs was working with the physical therapist, Ms. G was able to go down the 14 steps in her house and enjoy sitting out on her front deck. She went back and forth to the hospital periodically, but we were able to keep her home for a long time before Ms G’s care became too difficult for her family to keep up with and they could not afford to hire outside help so she had to go to a nursing home.

Mr. T

The second person I encountered on a home vent had such severe emphysema that he needed continuous ventilator support. He also had several other medical conditions that made his care more complicated: severe obesity and heart disease. I was feeling more comfortable from everything I learned from Ms. G, but unfortunately, his medical condition was much more tenuous. He was being admitted about every other month, mostly due to loss of consciousness or altered mental state.

He ultimately passed away, but I learned from him how a person on a ventilator can stay involved in family life. His bed was right in the living room and people were always passing through. While his wife was the main caregiver, he also had two very dedicated daughters who all shared the caregiving duties. He had a voracious appetite, and didn’t let the ventilator get in the way of him eating all his favorite foods.

Mr. S

Discharged from Dr. Greenough’s unit, Mr. S has a superhero son who is very confident and skilled with his hands. They also are able to have hired help for much of the day while the son is at work. The son was able to modify the house to keep the oxygen concentrator downstairs and run the tubing through the floor so that the loud noise it makes is muffled in the basement. Mr. S has been doing very well from a medical perspective. He needs vent support for only 12 hours per day due to a neurologic disease that caused diaphragm weakness. His son performs the trach changes with my assistance and his vent settings have not had to be altered.

Mr. S’s greatest struggle has been in adapting to life as a person who needs a ventilator. Even though he is able to be moved into a wheelchair for a few hours each day, his life became extremely limited very quickly and the emotional journey has been fraught. Mr. S tells me that he biggest struggle for him to be home on the vent has been getting a consistent caregiver during the day. While everyone needs to call out from work on occasion, a caregiver always needs to have a back-up.

Ms. B

Ms. B has a devoted daughter who is her excellent primary caregiver. Fortunately, this daughter works from home and is backed up by an aide from a private service. Ms. B has ALS that has progressed over the last year to the point where she has control of only eye movements. She is dependent on the ventilator 24 hours per day. Fortunately there are often young children in the home that make the environment cheerful and pleasant. Because she is home rather than in a facility, she is able to be included in family activities.

Ms. J

Ms. J is the most experienced with the ventilator. She’s been on the ventilator for about a decade, needing night-time support for central sleep apnea caused by a spinal cord disease. Ms. J is bed bound and has use of one arm and her head and neck, but despite this, is active and socially engaged. She’s able to use her phone as a lifeline to the world. She has much more experience than I do with the ventilator and this made our relationship dynamic interesting. She was teaching me most of what I was doing. She was also very hesitant to take any of my recommendations since she has become the expert on her own condition. It was necessary for her to become her own expert and advocate because, while she has a large and caring family, none are present in a consistent way to help take care of her. She has a hired aide from an agency, but this person, too, is not always consistent. It took several house calls before we built up the trust for her to allow me to make changes to her medication profile. She kept getting admitted for altered mental status, probably due to interactions between some of her medications and her ventilator setting also required adjustment. By working in partnership, we have been able to make some adjustments that will hopefully keep her at home.

I hope that soon, more people who need ventilators will be able to move back into their own homes. I look forward to working with this inspiring group of people. By studying, expanding, and spreading home-based medicine programs at Johns Hopkins and throughout the country, we will do our part in starting to provide the infrastructure necessary to help people on ventilators at home be successful.