Takeaway

Journalism and medicine have both taught me the privilege of having a voice and knowing when to use it.

Connecting with patients | June 18, 2019 | 5 min read

By Nadia Jajja, MBBS

In many ways I feel privileged to have had two completely different careers as a journalist and doctor, which over the years has allowed me to develop insight into the social and economic determinants of health, to view issues holistically, as well as with an emphasis on context. More so, acquiring patience, grit, and steadfast determination.

For instance, as a journalist, you learn early on that not all stories will make it to the printing press. You may have facts to lend credence, the human element to render emotion and engage the reader, and even moments of levity and hope, as you record heart-wrenching human tragedy, but sometimes some stories remain unfinished only to be remembered in other circumstances. There are plenty of reasons: paucity of editorial space, timing of opportunities, circumstances, and then cohesiveness of evidence. In cultures where fear pervades, journalism teaches you about the privilege of having a voice, and most importantly, when to use it.

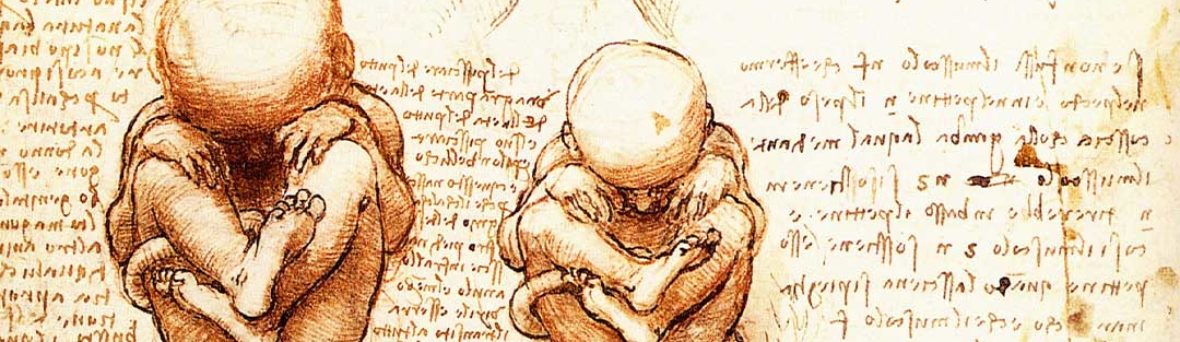

Those might-have-been stories linger around in your subconscious. In 2007-2008, an editor asked me to probe female feticide – selectively aborting female fetuses – a common and widely reported practice in India and China, though under-explored in Pakistan. The birth of a child is for many a joyous occasion, but in deeply patriarchal societies the birth of a girl child is not always welcome news. What we did know then with certainty was that cradles and cots set up outside orphanages and charities throughout the country received more girls than boys – for every 200 baby girls abandoned, 14 baby boys were abandoned.

At that time, I had newly transitioned to my clinical years in medical school, and the intersection of real medicine and journalism excited me. Medicine is similar to journalism in many ways: we interact with human beings sometimes during their most vulnerable moments, listen to their stories, and through our work attempt to uphold ideals and principles, or deliver exemplary care.

So that year, when I spoke with obstetricians leading national collaborations, sonographers, and patients, I learned about the nuances involved in a pregnancy ending – be it an abortion or miscarriage – in a politicized and religiously charged landscape. Contrary to popular belief, in Pakistan termination of a pregnancy up until the second trimester was not illegal provided it was for medically necessary purposes (physical or psychiatric), or put the life of the mother at risk. In this clinical and cultural context, some decisions to terminate pregnancy were easy (e.g. sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation), but others (sex selection, another child you could not afford), more difficult to explain. Even as a high-profile obstetrics care provider, you could very well be shunned by your peers in medicine for as much as suggesting a first or second trimester abortion, and hence referrals to abortion care providers were made quietly.

After a few weeks, we figured that there was plenty of evidence available about illegal and legal abortions – both widely reported – but no robust data on selective fetus abortions. We decided to leave the story at that.

I graduated and continued on with work and career.

And then in my internship year, my roles changed: from being a medical student and journalist I was now a junior doctor, from an impartial witness to an active participant in patient care. Whereas in journalism justice and equanimity are major themes, in medicine, with empathy and compassion comes the added burden for conclusiveness – there is no abandonment of people, patients, and projects. The first principle of care is do no harm. No more of the distancing effect that journalism afforded with its observations of people and places, stories unfolding without us influencing the ending.

For the first time, I felt how residents and teaching faculty navigated this incredibly difficult area of medical practice with ethical responsibility. In medical school, we learned the theory of how to break bad news, but how do you tell an expectant parent about chromosomal abnormalities, or the existence of severe anatomical defects and malformations without emotions involved? How do you tell an expectant parent that their child will not survive? How do you ask if they would rather terminate the pregnancy now or carry it to term? More questions than answers.

What remained consistent, whether it was working as a journalist or doctor, was the patriarchal attitude to female reproductive choices, and the visceral reaction men have to decisions about women’s bodies. As a reporter, you could have left at the end of the day, but as a doctor you would see the same parents (and attitudes) again.

Through working with and learning from my fellow interns and residents, I came to understand that as healthcare providers you have the power to question without hesitation certain decisions and practices, but knowing how to direct these conversations within an ethical and legal framework of the culture in which you are working, and when to step back and let women and couples make informed decisions, is crucial.

Communication across many cultures and languages takes times to develop, but there is one aspect that is critical to effective communication, which is authenticity. People will see and feel through you immediately if you are not authentic in your approach to difficult conversations and decisions. Setting aside one’s own personal beliefs, feelings, or prejudices, is a key skill to the practice of medicine, as well as staying in non-judgement. To do this, while remaining authentic to ourselves in our communication with patients and families, requires a lifetime’s work of practice.

I am years from both of these experiences. In retrospect I feel that journalism and medicine are uniquely aligned. More so, I am grateful for the opportunity to continue writing stories that illuminate and challenge preconceived notions and ideas, and that open out conversations about women’s reproductive health and rights, that are still so surrounded in taboo and misinformation.

Learnings:

1.) Good communication skills are essential in any career stream. Communicating means sharing clear messages and being understood even if you speak different languages.

2.) Work on your whole self – be authentic, compassionate, and have a moral compass.

3.) Use your privilege and knowledge to help your patients, but never be paternalistic in your interactions. Patients often know best.