Takeaway

We have much to learn from those who came before us. One example is working toward equity in healthcare, including fighting sexism and racism.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | May 3, 2022 | 5 min read

By Ralph Hruban, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

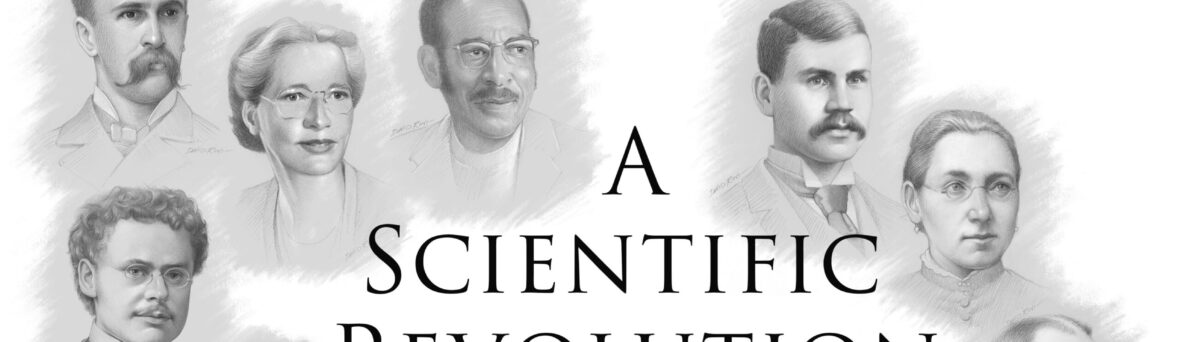

William Osler advised us that “It is only in the light of the past that we can hope to solve the problems of the present, and the future.” That’s why, during the pandemic, I’ve turned to my passion for the history of medicine for guidance. In fact, I’ve gone so far that with fellow Hopkins alum Will Linder, I recently published A Scientific Revolution: Ten Men and Women Who Reinvented American Medicine.

10 clinical excellence pearls from medical history

Our book focuses on the life experiences of 10 women and men. Each has important lessons to teach us about facing adversity and being the best healthcare professionals we can be. Beginning with this website’s namesake, our inspirational 10 include:

William Osler: Bedside teaching and love of humanity

We’ll always remember Osler for his dedication to bedside teaching and his humanistic philosophy. Teaching on the wards forever transformed medical education and patient care. And Osler’s love of humanity, summed up in his advice to recognize “The poetry . . . of the ordinary man, of the plain toil-worn woman, with their loves and . . . their sorrows,” remains a constant inspiration as we care for patients in today’s complex healthcare system. From Osler we can learn the importance of treating the patient, not the disease, and how best to serve our fellow man.

Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Equity and excellence

When Johns Hopkins University was nearly broke and lacked the funds to open a medical school, Garrett used hardball philanthropy to guarantee that women would be admitted to the medical school on an equal footing with men and to dramatically raise entry standards. Her insistence on the inclusion of women and the high bar for admission dramatically improved the training of doctors in this country. Garrett’s life teaches us that minimizing disparities often demands decisive action and that high standards are essential to delivering quality care.

John Shaw Billings: Medicine for a new century

A Civil War surgeon, who after Gettysburg wrote to his wife, “I am utterly exhausted mentally and physically . . l and am still hard at work,” Billings never operated again after the war. Instead, he tirelessly focused on “making order out of chaos.” He laid the foundations of the National Library of Medicine, was the chief designer of Hopkins Hospital, created the catalogue that became PubMed, built the Library of the Surgeon General’s Office that became the National Library of Medicine, and invented a punch card system that led to the establishment of IBM. From Billings we can learn that in medicine, as in so many other fields, effective information management is often the key to successful outcomes.

William Welch: Medicine through the lens of science

The son of a country doctor, Welch had a keen intellect and an extraordinary ability to influence his peers. As the first professor and dean of the medical school, he used these gifts to spread the gospel of scientific medicine. Despite his outward gregariousness, Welch never let anyone get close to him, likely because he may have been gay at a time when homosexuality was not accepted. Welch’s life teaches us about compassion and the power of viewing medicine through the lens of science.

William Halsted: Victory from defeat

Probably the most important and innovative surgeon from America, Halsted paid a terrible price for investigating the anesthetic power of cocaine. He chose to experiment on himself and soon became an addict. Despite this crushing burden that he always kept hidden from others, Halsted pioneered a host of innovations. From Halsted we can learn the importance of “safe surgery” and the power of residency training.

Jesse Lazear: The ultimate sacrifice

This young Hopkins-trained microbiologist paid with his life for a breakthrough in the struggle against a virus. Lazear joined the U.S. Army board tasked with wiping out yellow fever in Cuba. He allowed himself to be bitten by a mosquito that had fed on an infected soldier in a daring self-experiment to prove that this insect was the vector responsible for the spread of yellow fever. 12 days later, fever-wracked, delirious, and vomiting, Lazear died. Lazear’s tragic death reminds us that medical advances often come at the cost of great sacrifices.

Max Brödel: Art applied to medicine

A German immigrant, Brödel has been called the greatest anatomic illustrator since Leonardo da Vinci. The clinical advances of his peers wouldn’t have won the worldwide recognition they earned in the early twentieth century had it not been for Brödel’s astonishingly lifelike illustrations. From Brödel we learn to appreciate the role that non-physicians play in medicine.

Dorothy Reed Mendenhall: Hardship and discrimination

Sexism blocked Reed throughout her life. As a graduate fellow at Hopkins, she characterized the cell that causes Hodgkin disease. Her reward? Reed was passed over for a faculty position in favor of a man who had done little. She lost her first baby to cerebral hemorrhage caused by an incompetent obstetrician. Reed endured these painful setbacks to go on to a distinguished career as an expert advocate for preventive care for mothers and babies. Reed Mendenhall’s life teaches us about resiliency and perseverance in the face of hardship.

Helen Taussig: Founder of pediatric cardiology

Decades after Reed battled sexism in medicine, Taussig faced the same barriers. She was known for her tenderness with her young patients but was tough as nails with men who didn’t treat her as an equal. Taussig initially faced deep skepticism from surgeons about a novel procedure she envisioned to save babies born with tetralogy of Fallot. Several years later, she stood by the operating table when the first “blue baby operation” was performed. Taussig inspires us with her determination to fight for her ideas—and her patients—even in the face of sexism.

Vivien Thomas: Battling blatant racism

The only one of our 10 exemplars to be the subject of a Hollywood movie, Thomas was a high school-educated lab technician and the grandson of a person who was enslaved. He battled blatant racism, but went on to perfect the surgical techniques that opened the path to pediatric heart surgery, and to teach surgical techniques to a generation of surgeons. When Dr. Rowena Spencer was asked where she learned her beautiful surgical technique, she replied, “From a Black man with a high school education.”

Lessons for today:

Clinical pearls are often stand-alone bits of wisdom useful in improving patient care. What the two kinds of pearls have in common is that they are based on lived experiences. We can all benefit from reflecting on these exemplary lives in two ways. First, they ground us in the attitudes and behavior that are essential to overcoming challenges in our work as healthcare professionals. And second, these shared stories bring us closer together as a community.

This piece expresses the views solely of the author. It does not necessarily represent the views of any organization, including Johns Hopkins Medicine.