Takeaway

There are a number of important physicians in history, and an appreciation of our past can further our quest for clinical excellence in the present.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | April 2, 2019 | 5 min read

By Lee Akst, MD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

“Of all the pure specialties, that is to say, those branches requiring special technique and special instruments and methods of precision, laryngology is the most generally useful to the diagnostician and general practitioner.” ~ John Noland Mackenzie, The Teaching of Laryngology in Johns Hopkins University, 1906.

Many of us know that the “Big Four” founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1889 were William Henry Welch, William Osler, William Stewart Halsted, and Howard Kelly – giants in the fields of pathology, medicine, surgery, and gynecology respectively.

But did you know that among the initial faculty at Hopkins was a laryngologist, John Noland Mackenzie? Or that Laryngology was a large part of the initial clinical service line and educational curriculum in the formative years of both Johns Hopkins Hospital and the School of Medicine?

As Johns Hopkins Hospital was formed in 1889, there were initially nine divisions:

1) The Department of General Medicine, directed by William Osler

2) The Department of Diseases of Children, directed by William Osler and W.D. Booker.

3) The Department of Nervous Diseases, directed by William Osler and H.M. Thomas.

4) The Department of General Surgery, directed by William S. Halsted and John M.T. Finney.

5) The Department of Genitourinary Diseases, directed by William S. Halsted and James Brown.

6) The Department of Gynecology, directed by Howard A. Kelly and Hunter Robb.

7.) The Department of Ophthalmology and Otology, directed by Samuel Theobald and Robert L. Randolph.

8) The Department of Laryngology, directed by John N. Mackenzie.

9) The Department of Dermatology, directed by R.B. Morrison.

It’s this eighth division, the Division of Laryngology directed by John Noland Mackenzie, that’s the subject of this essay – not because, as current Director of Laryngology at Johns Hopkins, I’m arguing for restored primacy of Laryngology among the various specialties at the School of Medicine, but because a look back at where we’d been helps to affirm our current focuses on clinical excellence, multidisciplinary care, and education.

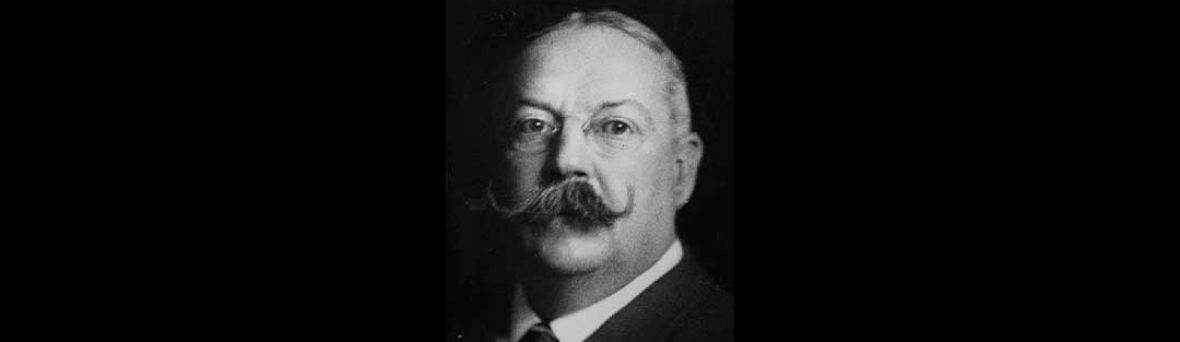

John Noland Mackenzie (1853-1925) was born in Baltimore and received his medical degree from the University of Virginia in 1876. Subsequent studies included time spent training with Clinton Wagner in New York, Max Oertel (inventor of laryngeal stroboscopy) in Munich, and Morell Mackenzie (the world’s preeminent laryngologist at the time, and no relation) in London. Upon his return to Baltimore, Mackenzie served as Professor of Laryngology at the University of Maryland (1887-1897) and Johns Hopkins (1889-1912). He is considered a pioneer in American laryngology, and served as President of the American Laryngological Association in 1889. Though later associated mostly with the nasogenital theory that erectile tissue within the nose, leading to nasal congestion, was related to erectile tissue of the genitals (a theory later championed by many other physicians, including Sigmund Freud and now discredited), his work in Laryngology remains available to us through writings which remain available online today – for example, “Some Reminiscences, Reflections, and Confessions of a Laryngologist” (Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 25(1):1916, 61-91).

Under Mackenzie’s tutelage, laryngology became an obligatory part of the medical education curriculum. Every Johns Hopkins medical student of his time rotated through the Laryngology Division, and each needed to pass an examination in laryngology to receive their degree. Consider at the time that many laryngologic diseases of the era were infectious in nature – laryngeal manifestations of tuberculosis and diphtheria were common, and laryngeal cancer remained rare until the advent of mass-produced cigarettes as smoking was an expensive habit limited to the upper class. Consider as well that oropharyngeal exam and mirror laryngoscopy were the only ways that physicians of the time could routinely examine the interior of the body, as other physical exam and diagnostic techniques of the time achieved external views only. In this era, Mackenzie argued that “it is impossible to exaggerate the importance of the laryngoscope to the medical and surgical diagnostician in the early detection of disease, not only in the respiratory organs themselves, but, of equal, if not superior importance, in the neighboring and remote organs of the body” (Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 1916).

Clearly, as medicine and medical education have evolved, Laryngology is no longer >10% of the curriculum nor clinical practice of the hospital. However, the lessons taught to us by Mackenzie persist. He argued in 1916 that “the common use of laboratory tests have, by opening up a lazier and easier road to diagnosis, greatly dulled the former diagnostic sense and diagnostic acumen” – and were he here today, he’d still be emphasizing “the importance of the laryngoscopic or naked eye method of diagnosis (supplemented or not, as the case may be, by clinical phenomena) to exclusion, if possible, of the microscope and the laboratory in the detection of disease in the larynx” (Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 1916). These words resonate with my practice now, as I exhort residents and fellows to take a good history, to listen carefully to the patient’s voice, and to generate a differential diagnosis on the basis of physical exam before performing any confirmatory testing. Similarly, Mackenzie’s awareness that Laryngology intersects with so many other disciplines – “no department of medicine is isolated and independent, but they are all mutually dependent and co-ordinate” (Laryngoscope 1906) – is as true today as it was then. As I think about the last week in my practice, I can recall consultations from spine surgeons, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, neurologists, and pulmonologists with concern for the vocal function of their patients, as laryngeal complaints served as an indication of overall disease.

In these ways, the words of Mackenzie from more than one hundred years ago ring in my ears – recalling my current clinical behavior to best practices of careful history and exam, awareness of the interaction between laryngeal disease and overall health, and emphasis on teaching these paradigms to the next generation of physicians. Though the name of this website focuses on Osler, it’s worth remembering that there are a number of important physicians in history, and that an appreciation of our past can further our quest for clinical excellence in the present.