Takeaway

Clinical learning and practice are not removed from cultural and political realities. As clinical educators, it is our responsibility to create both humanistic learning environments that inculcate respect for the ultimate purpose of healthcare: the well-working of the human being as a whole.

| September 18, 2019 | 7 min read

By Flora Smyth Zahra, MA Clin Ed, DRestDent RCS, FHEA, Kings College London, Margaret Chisolm, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

This is the eighth in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients). Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in August.

Dr. Smyth Zahra

I found it inspiring once again, to join over 4,000 health profession educators from all corners of the globe at the Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) annual conference in Vienna, Austria. It was particularly gratifying that “humanities” was one of this year’s conference themes, reinforcing that reintegration of humanities into clinical curricula is becoming more mainstream. Wherever the conference is held, amidst the sheer number of delegates, it’s always reassuring to see the familiar faces of the AMEE staff welcoming us back into the fold and our educational community of practice. Transferrable as the AMEE brand is, year after year and impressive in scale, the conference serves as a powerful reminder that learning cannot be isolated from the cultural, is inherently socio-political, and, crucially, context dependent.

“No one is born fully-formed: it is through self-experience in the world that we become what we are.”

-Paulo Freire

In between plenaries, symposia, and workshops, I set aside time to visit the Klimt paintings that Vienna has become synonymous with. En route from the conference center to the Leopold Museum, I turned a corner and found myself in the large square pictured below. Perhaps it was the dental office on the corner with its Art Nouveau signage, the olive trees outside the café, or just the pleasant sense of light and space beyond the conference center the square afforded that beckoned me forwards. It may also have been the statue of the poet, or the female figures of the cardinal virtues—Prudence, Fortitude, Temperance, and Justice, at the entrance to the Austrian Supreme Court that drew me in, but then, I became aware of a squat, bunker-like brutalist block.

Closer examination revealed an inaccessible library—no doorknobs on the concrete doors, shelves upon shelves of books with their spines turned inwards, therefore impossible to identify by title, let alone read. Walking around the structure, the names of infamous concentration camps were clearly engraved on the stone plinth together with the uncomfortable reminder that 65,000 Austrian Jews were sent to their deaths. I was standing in the Judenplatz. This starkly shocking memorial by British artist Rachel Whitehead, cast in relief, portrays a library full of individual editions of the same book each with their own narrative that is impossible for us to read or know. It is deeply disturbing simply because in our current time, its austere lines remind us that, as Pablo Picasso said, “Art is the lie that enables us to realise the truth.”

I couldn’t sit by those olive trees for coffee after that, and in fact never made it to the Leopold. Context is crucial—our learning environments are not removed from cultural and political realities. As clinical educators, it is our responsibility to create both humanistic learning environments that inculcate respect and tolerance for others and transformative learning opportunities that at times are uncomfortable for our learners, but that provoke them to think critically for themselves and to interrogate their surroundings for the good of their patients, their colleagues, and themselves. This shouldn’t just be left to the artists alone.

“Teaching is the practice of freedom.” -Paulo Freire

Dr. Chisolm

In August, I too traveled to Vienna, Austria, for the annual AMEE meeting, where I visited the and the Leopold Museum and the Kunts Historiche Museum Wien, both with spectacular art collections. However, the most moving art I saw wasn’t found in a museum but on a tour of Art Nouveau architectural sites in Vienna. One of these sites was St. Leopold church, commissioned as part of the part of the large Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital complex. The church was built between 1903 and 1907 by Otto Wagner, one of the most renowned Austrian architects and an important member of the Vienna Secession art movement. Although Wagner designed the church out of his desire to escape traditionalism, he also designed this Art Nouveau masterpiece with the needs and desires of the patients it exclusively served in mind, a remarkable gift to these often forgotten members of our community. For instance, Wagner paid close attention to the building’s light and ventilation to ensure these elements provided a sense of calm and rejuvenation, and he designed the holy water stoops at the entrance to provide a constant stream of running water to avoid the spread of germs.

St. Leopold’s Church is open to the public during limited hours, including for the Sunday mass still celebrated there, and for private tours like the one I took. Located atop a hill, the first thing you see as you approach is the church’s giant, golden dome (from 2000 to 2006, the cupola was newly plated with gold leaf). As you get closer to the entrance, the four columns topped by four thoroughly modern bronze angels come into view. These monumental statues are considered some of the best examples of Art Nouveau sculptures in the world (and were also part of the recent restoration). Above this row of angels with their bobbed hairstyles, sit two saints—including St. Leopold himself—on square chairs designed in the style of Wagner’s fellow Secessionist artist, Josef Hoffman.

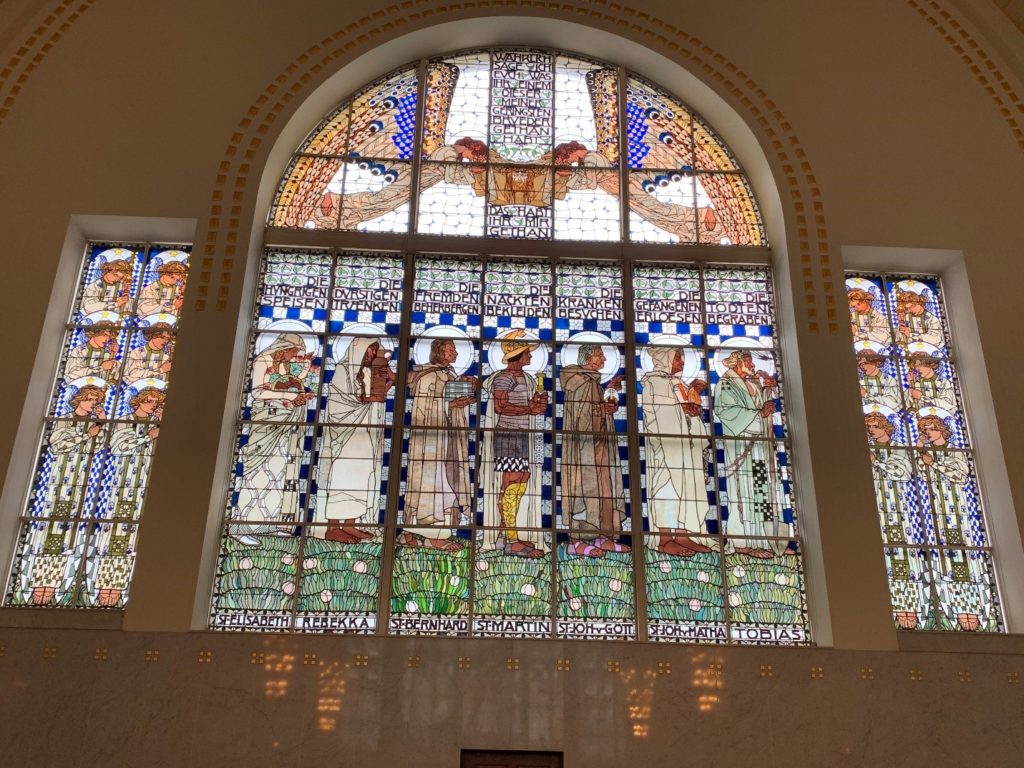

Moving inside the church, the modern elements continue, including mosaics, metalwork, and stained glass windows portraying seven saintly protectors of the poor and mentally ill. The window to the left of the altar depicts the corporal acts of mercy—to feed the hungry, give water to the thirsty, to clothe the naked, to shelter the homeless, to visit the sick, to visit the imprisoned, and to bury the dead. The window to the right, the spiritual acts of mercy—to instruct the ignorant, to counsel the doubtful, to admonish the sinners, to bear patiently those who wrong us, to forgive offenses, to comfort the afflicted, to pray for the living and the dead. Most remarkably, the altar itself depicts saints who represent the spectrum of illnesses for which the patients have been hospitalized, such as St. Dymphna, the patron saint of people with epilepsy. Although not a believer, by offering the gift of this stunning church to the patients at this psychiatric hospital, Wagner engaged in his own acts corporal and spiritual acts of mercy. Wagner’s creation of a space filled with light and beauty—specifically for patients with psychiatric illness separated from the rest of society—reflects a deep respect for the inherent worth and dignity of every human being, including those suffering from mental illness.

Photograph by Margaret S. Chisolm

The visit to this lovely, sacred space would have been meaningful enough; however, what followed rendered the beauty of this church even more poignant. As we walked down the hill from the church towards the hospital buildings, we stopped by a rose garden that is studded with nearly 800 columns of light. It turns out that, during the Nazi regime, 7,500 patients with psychiatric illness—including 789 children—were deemed unworthy of life, and so were experimented upon and “euthanized” by the doctors, one by one. In this memorial—erected in 2000—each light column represents one of these 789 systematically murdered children. A sobering lesson in the heights and depths of human potential, all in one spot. A church built to nurture the spiritual lives of patients with psychiatric illness, and a hospital and its doctors dedicated to taking those lives away.

As a psychiatrist who opposes physician-assisted death, this month’s half-day of looking closely at art offered a profound lesson in how the purpose of medicine and the role of a physician can become corrupted. The visit also reminded me of something the anthropologist Margaret Mead wrote to a psychiatrist friend of hers:

“The followers of Hippocrates were dedicated completely to life under all circumstances, regardless of rank, age, or intellect—the life of a slave, emperor, foreign man, defective child. . . This is a priceless legacy which we cannot afford to tarnish. But society has repeatedly attempted to make the physician into the killer… It is the duty of society to protect the physician from such requests.”

Stay tuned to CLOSLER for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in September.