Takeaway

Patients face medical decisions constantly. Assessing capacity for decision-making protects their autonomy.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | March 16, 2020 | 4 min read

By Elizabeth Ryznar, MD, MSc, Johns Hopkins Medicine

Part 1: Could you help?

“Could you help? I’m worried my patient has a pulmonary embolism and she is refusing CT and V/Q scan,” the hospitalist said.

Assessing capacity when a patient refuses an important medical intervention is a common situation for consult psychiatrists. Legally, any physician can assess capacity; however, in difficult situations, it may be helpful to have a psychiatrist’s input.

Capacity thresholds

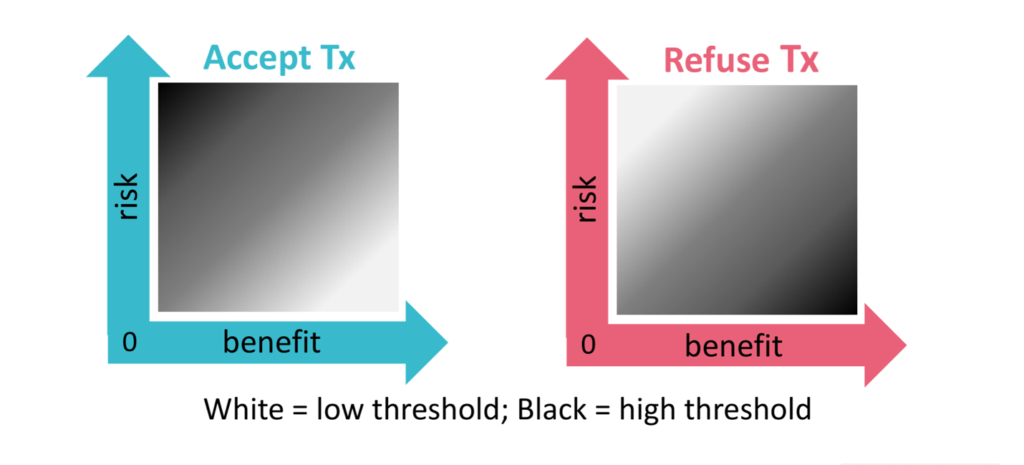

The first step of any capacity evaluation, before speaking to the patient, is assessing the medical situation. Capacity is dynamic, not fixed. The degree of capacity a patient needs to demonstrate in accepting or refusing an intervention depends on the risk-benefit profile of the intervention. Agreeing to a high benefit / low risk procedure requires a lower threshold for capacity than a agreeing to a high benefit / high risk procedure or low benefit / high risk procedure (see diagram below). A lower threshold for capacity means that the justification need not be as robust for each of the four components of capacity (choice, understanding, appreciation, reasoning).

In this clinical example, both procedures had high benefit: detection of pulmonary embolism (PE), which can be life threatening, in a patient with new-onset tachycardia and PE risk factors without any other explanation for the tachycardia. The risk with computer tomography (CT) PE is low to moderate (the risk of contrast allergy or acute injury for CT PE, along with potential discomfort or inconvenience from the procedure), whereas the risk of a ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan is very low (potential discomfort or inconvenience). Therefore, refusing the VQ scan would require a very high capacity threshold, while refusing the CT PE would require a moderate capacity threshold.

Capacity Components

Once the threshold has been established, you must see if the patient meets that threshold by evaluating the patient’s decision-making process. A patient has capacity if he or she can demonstrate the four functional components of capacity:

1. Expressing and sustaining a choice.

2. Understanding the medical condition and risks/benefits of the intervention as well as its alternatives, including no intervention (this presupposes that the patient has been informed of his or her condition in a way that he or she can understand).

3. Appreciating the medical condition, which entails acknowledgement of having a medical condition (insight) and the impact of the choice on one’s life, and

4. Reasoning through the various options before coming to a decision.

In speaking with the patient, it was clear that she did not have capacity to refuse treatment. Although she demonstrated a consistent choice (refusal) and basic understanding of tachycardia and its potential causes, she lacked appreciation and reasoning. Specifically, she attributed her tachycardia to a long-standing somatic delusion of missing internal organs and she did not believe that a blood clot was even a remote possibility in her case.

I spent an hour with the patient, not only explaining the reason for the desired intervention and evaluating her decision-making capacity, but also listening to her, holding her hand, and validating the distress of her belief that she is missing organs without actually supporting the delusional thought itself. As we finished the conversation, she changed her mind and agreed to do the V/Q scan.

However, the case was far from closed.

Part 2: Good news and bad news

“There’s good news and bad news,” I tell the consulting hospitalist. “She agrees to the V/Q scan, but she does not have capacity to make the decision.”

Although agreeing to a high-benefit, low-risk procedure requires a very low threshold for capacity, the patient still needs to demonstrate all four components of capacity. Because the patient could not appreciate the possibility of the blood clot and steadfastly believed the only problem was her missing organs, she did not pass the low bar. Therefore, she lacked the capacity to consent.

The distinction between assent and consent

This distinction between assent and consent is important. Capacity evaluations test whether a patient has the ability to make a decision, and this ability is one of the core elements of informed consent (along with receiving appropriate information and being free from controlling influences). Thus, capacity is firmly tied to a fundamental pillar of medical ethics: patient autonomy. In this case, the patient did not have the capacity to make the choice and therefore could not provide informed consent. It is also possible that through an empathic connection, she was coerced into the decision. Therefore, it was necessary to seek a surrogate decision-maker.

Protecting patients

It may seem like taking a patient for a V/Q scan without full capacity may not be significant, especially because the test was suggested with good intent and is relatively benign. However, even though a physician deems an intervention to be important, the decision may be incongruent with a patient’s long-standing values. Physicians (who do not have a long-standing relationship with the person) do not know those values, and thus state law delineates a list of surrogate decision-makers, starting with spouses and close family members. Furthermore, there have been several historical abuses of power in medicine (some examples were litigated in Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital and the Nuremberg trials), which explains why Western medicine values patient autonomy.

In conclusion, a capacity evaluation is important because it safeguards a patient’s autonomy and prevents abuses of power. The exemplary clinician should always assess (either explicitly or implicitly) a patient’s decision-making capacity, no matter if they are accepting or refusing an intervention.

Acknowledgements:

The author thanks Dr. Durga Roy for her constructive comments on this post.