Takeaway

The skills required in the clinic are the same as those in the art gallery: to examine, investigate, embrace ambiguity, consider multiple interpretations, reflect, collaborate, and learn.

This is the seventh in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients). Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in July.

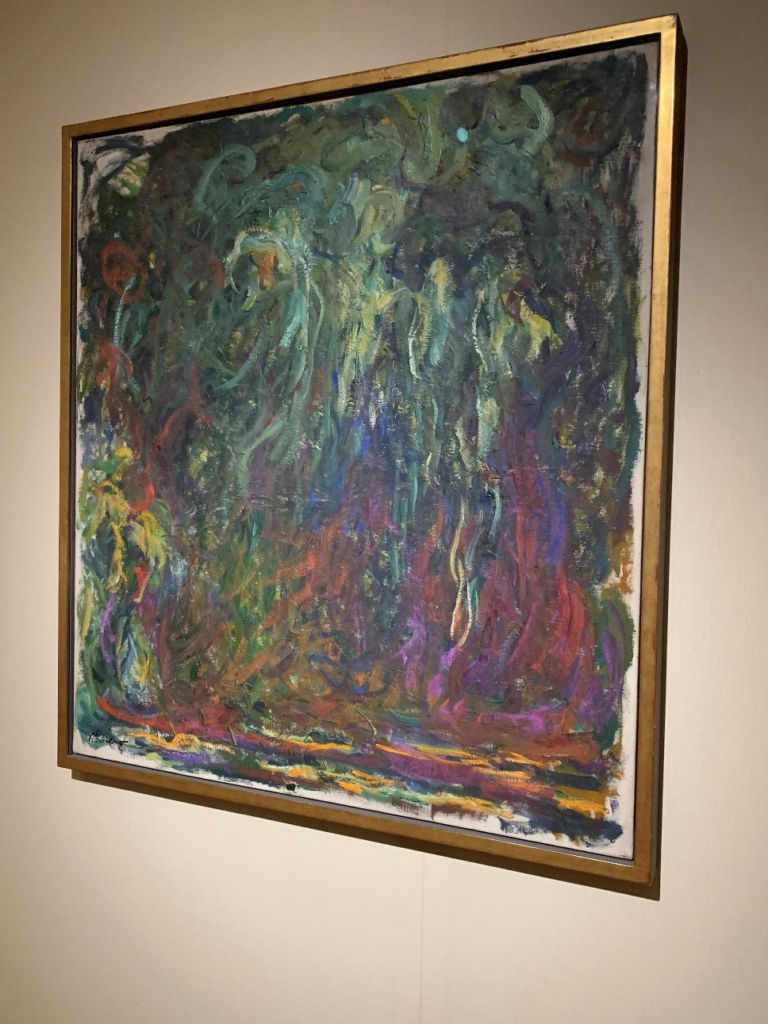

“Weeping Willow,”Claude Monet, 1920-22, Collection of the Musee d’Orsay, Paris.

Photograph by Margaret S. Chisolm

Dr. Chisolm:

In July, I traveled again to Fort Worth, Texas for a quarterly research meeting. Arriving early, I was able to squeeze in a return visit to the Kimbell Art Museum. The Kimbell’s original cycloid-vaulted building – designed by Louis I. Kahn – is an architectural destination in itself. But I was there to see a special exhibition in the colonnaded pavilion (designed by Renzo Piano) situated on the main (west) façade of the Kahn Building. On this visit, I noticed the lovely, rectangular pond along the west façade. It was filled with brightly colored water lilies, a fitting introduction to the exhibition I was there to see: “Monet: The Late Years.”

Arranged chronologically and thematically, “Monet: The Late Years” focuses on a time in Monet’s life marked by deteriorating eyesight and the loss of his second wife, Alice, and eldest son, Jean. Walking through the galleries, I could see how Monet, as his vision was failing due to cataracts, took refuge in familiar places. From his outdoor studio at Giverny, he painted multiple versions of the Japanese footbridge and lovely rose-covered trellises that traversed the path leading from his house to the garden. After his wife and son’s deaths, Monet took a hiatus from work, returning – in 1914 – to paint a vibrant series of water lilies, as well as some very large mural-style paintings and more water lilies, all on display at the Kimbell. However, the series of weeping willow paintings that I found in the final set of dark and intimate galleries was, for me, the highlight of the show. Several of these paintings were being shown in the United States for the first time, and the number of paintings displayed together – six – was unprecedented. However, it was not these facts that moved me.

With the weeping willow series, it seems that Monet was mourning for both himself and the whole world. The willow trees are bent low by more than the weight of Monet’s own losses; these are not merely veiled self-portraits. Yes, Monet’s cataracts were significantly altering his visual perception. And yes, Monet’s second son had left for World War I, in the wake of Monet’s first son’s death. But, by 1918 – the end of the War – over 36 million people had lost their lives (counting both civilian and military casualties), making it one of the deadliest conflicts in the history of the human race. The weeping willow series is about much more than personal loss; it is a reflection of loss on a global scale, and on humanity. However, the weeping willows are also about the human spirit’s ability to triumph over adversity. Because it is with this series of paintings that Monet produced his most pioneering work.

My favorite painting in the entire exhibition is one of the last that Monet ever painted. Completed in 1922, when Monet was about 82-years-old, “Weeping Willow” (from the collection of the Musee d’Orsay, Paris and in the United States for the first time) looks like a work of abstract expressionism from the mid-twentieth century. With its vibrancy of motion and color, this “Weeping Willow” is a testament to Monet’s persistent vitality in the face of adversity. Monet passed away in 1926. That he could create such a painting – one that transforms the bent and worn weeping willow into a vital force of nature – in the very last years of a long life is an amazing lesson for all of us.

Monet’s life and work teaches us many things about what it means to be human, not the least how we and our patients can – despite grave losses – continue to lead a life full of discovery and meaning to the very end.

Dr. Smyth Zahra:

All of us who live, work, or study in the area enjoy the museums and galleries in and around the Strand and Guy’s campuses at King’s College. There is growing evidence of the benefit of these liminal spaces to health and wellbeing.

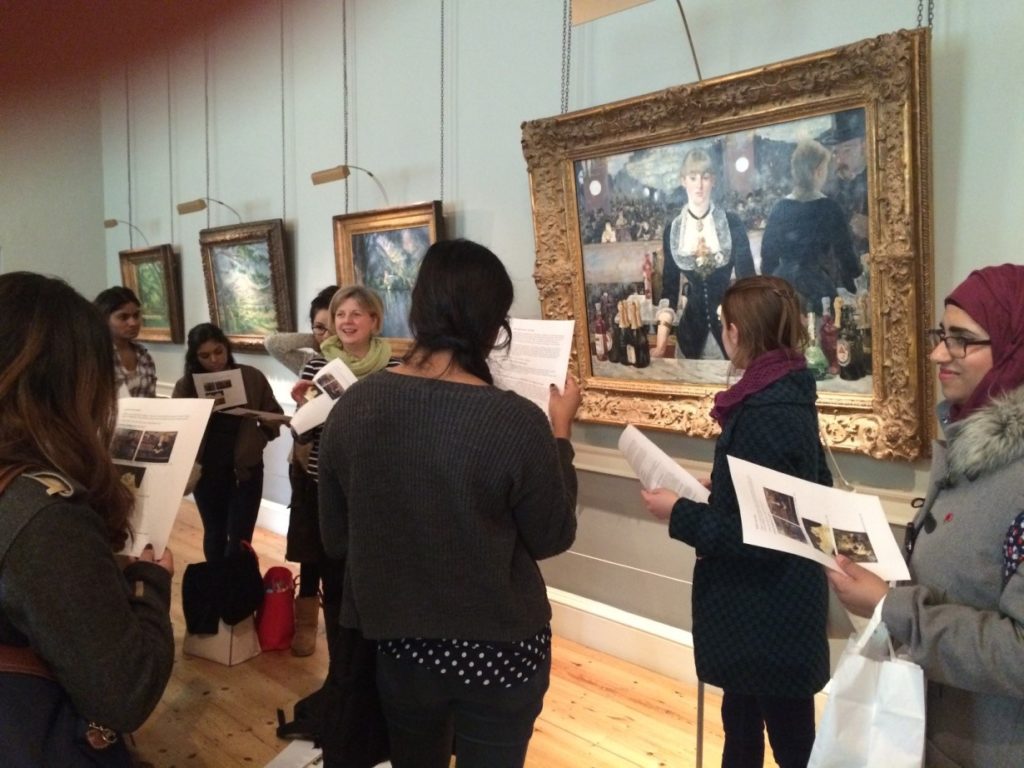

My own favourite, “The Courtauld Gallery,” is temporarily closed until 2021 whilst it undergoes major transformation at its Somerset House location. It was here that I took some of my Clinical Humanities dental students when I first started researching the potential value of integrating arts and humanities into clinical curricula supported by the King’s Cultural Community.

The students’ favourite piece on that visit (currently touring in Japan) was Edouard Manet’s final painting: his depiction of Suzon, one of the barmaids at the “Folies-Bergère.” The students had two minutes to look at the picture in silence followed by group looking and discussion. Manet was introduced as a realist artist, a revolutionary of his day. Dr. Kate Dunton went on to explain that this wasn’t about what you know, but about what you see, feel, can figure out by looking, and are curious about. The group was encouraged to observe closely by asking the following sorts of questions:

What do you see? What else? What do you make of that? Anything else? What’s going on here? If this were a still from a film, why would this be a significant moment? What do you see in the picture that tells you that? How would you describe the atmosphere and mood? What do you see in terms of the light, colour and texture that makes you say that?

In our “culture of certainty” that dental education too often propagates,we deliberately chose this particular painting so that the group would pause, consider, and embrace the ambiguity of perspective by looking closely at the reflection of the man in the mirror. Further observation of the many details of the painting led to a discussion of the politics of the time, the detached expression of Suzon’s face, her demeanour, and provoking questions about her role in society and concern for her welfare.

Close observation is crucial to both art and dental practice. Diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning rely on interpretation of the patient’s presenting complaint, their medical history, and close observations made during their examination. Presenting signs and symptoms are not always straightforward, just as, at first glance interpreting a piece of art may be difficult and require discussion and further advice. There are obvious aesthetic parallels between art and dentistry: symmetry, balance, tone, hue, texture, colour, the harmonising of hard and soft tissues. Edouard Manet was quoted as saying:

“There’s no symmetry in nature. One eye is never exactly the same as the other. There’s always a difference. We all have a more or less a crooked nose and an irregular mouth. I paint what I see, and not what others like to see.”

The visual skills and powers of observation required in the clinic are the same as those in the art gallery, but because art is not explicit and two people can look at the same painting and walk away with different views, art can help us practise dealing with and accepting ambiguity. Away from our patients, scaffolded teaching in the gallery allows us to examine, investigate, hone visual and observational skills, discuss multiple interpretations, problem solve, and reflect, collaborate, learn, and support each other as a team.

Stay tuned to CLOSLER for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in August.