Takeaway

Innovative dementia care designs raise moral questions about whether deception of patients is ever ethical. The clinically excellent physician tries to avoid deception at all costs.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | January 27, 2020 | 3 min read

By Diana Anderson, MD, MArch, Clincial Geriatrics Fellow, University of California, San Francisco

The Seven Lamps of Architecture, written in 1849 by the English art critic and theorist John Ruskin, embodies the principles that good architecture must meet. One of the lamps is truth. Do our dementia care designs break this core architectural value?

Truth can be represented and perceived in different ways in architecture. Architects have been using visual trickery throughout history; trompe l’oeil (French for “deceive the eye”) perspective techniques were first used in the medieval period and increasingly common during the Renaissance where walls, ceilings, and domes were painted with designs that “trick” the observer into seeing other features such as windows, columns, and stonework.

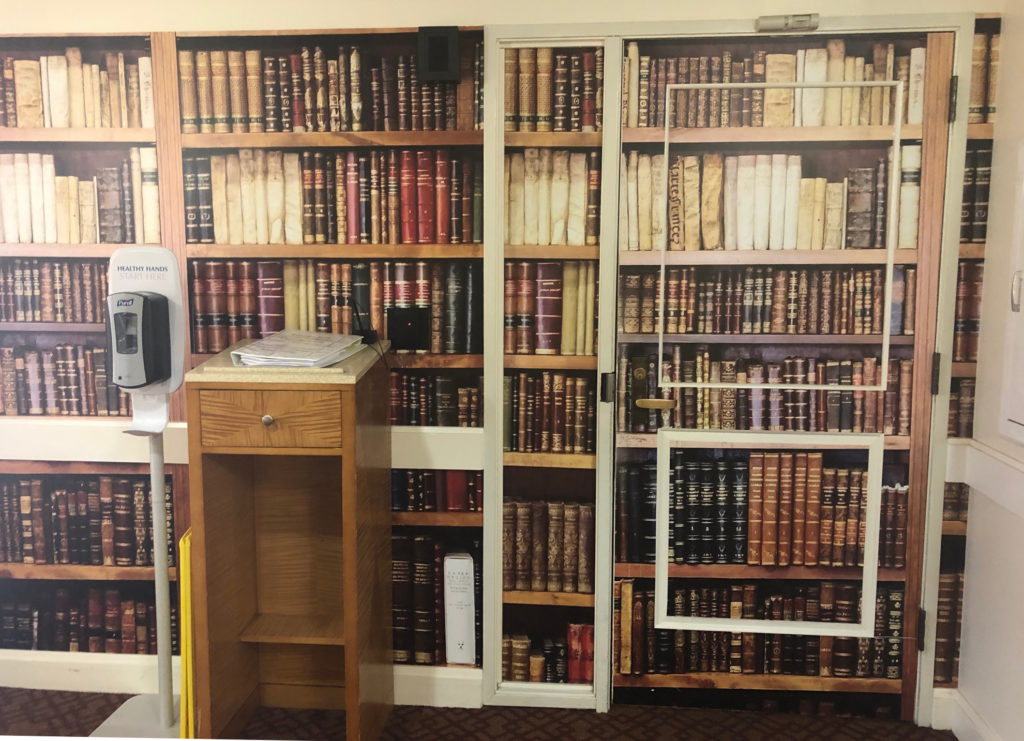

The environmental features we design for in settings where people with dementia live or are cared for often leverage the building as a restraint—secure units within nursing and care homes, with doors painted trompe l’oeil to look like bookcases or other immovable objects to prevent patients from leaving. Is it okay to “fool the eye” of a cognitively impaired person?

The “dementia village” has become a design alternative to a secure unit whereby residents can wander freely outside living quarters to access amenities, outdoor space, and social gathering sites. Anecdotal reports note decreased use of psychotropic medications and lower incidence of behavioural disturbances. Staff are present in regular street clothes and cameras monitor, with a perimeter that is, ultimately, gated or locked. That sense of freedom is a design illusion. Is this less problematic than the stigma of a “locked ward”? Is one building type inherently better than the other is, and how do we make that determination?

When and how to honor truth in dementia care design forms a moral grey area in healthcare architecture. In the “Lamp of Truth” Ruskin demands morality in architecture. However, he makes a distinction between artistic deception and imagination, “…as spiritual creatures, we should be able to invent and behold what is not.”

He then cautions, “…as moral creatures, we should know and confess at the same time that it is not.”

We presume that the dementia village does not appear illusionary to those within it, so there may, in fact, be value in designing certain untruths.

The spa-like trend of hospital design conceals medical equipment to instill calmness, but what if our illusion increases anxiety given that users’ awareness of the space they are in? Is the dementia village design any different? Do the village designs erode the honesty of the care providers?

As clinicians, it is important to increase our awareness of built environments for health. Clinicians can advocate for patients by considering their surrounding environment—consciously take note of the access to daylight, acoustic control, and promotion of mobility and space for caregivers. Discuss and explain environmental choices to families—clarify that designs have been developed for the benefit of the patients and ask for caregiver feedback and observations. Through our increased attentiveness and discussion, architecture can become a tool in raising awareness on dementia care.

While Ruskin’s truth referred mainly to materiality and an honest display of construction, consider the intangible truths conveyed by designs related to maximizing health and happiness. Because dementia affects people differently and we have yet to understand someone’s experience or reality from within, we do not yet have consensus on design illusion in dementia care. While designs might plan to deceive, our goal should always be to choose the least potentially harmful design method—architects must act in the best interests for people and meet users in their current truth.