Takeaway

The art museum is a space that has lessons to teach about clinical excellence, and fosters both the personal development and professional identity formation of clinicians.

This is the fifth in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients). Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm are participating in an Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month looking at art. This is the story of what they did in May.

Dr. Chisolm

In May, Flora and I returned to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, along with the other AMPHE fellows and course directors from the Harvard Macy Institute. We had last been together in January for two full days of experiential learning about how to use an art museum as a teaching laboratory. And now, all 12 fellows had returned to the Museum to practice some of the methods we had learned in January, and to try our hand at some new ones.

Nine of us had arrived a couple of days earlier, to participate in an optional two-day workshop in facilitating ‘interpretative conversations,’ a la visual thinking strategies (VTS). I was one of the nine who then had the good fortune to be able to spend four full-days exploring the Museum’s over 200,000 square feet of gallery space and looking at a lot of art. The Art of the Americas wing alone displays over 5,000 works of art in its 53 galleries and I strolled through one of these, Gallery 232 (pictured above), several times a day.

The central feature of Gallery 232 is a very large (over 7×7-feet) oil painting by John Singer Sargent of four girls, daughters of Edward Darley Boit and Mary Louisa Cushing Boit. It is an arresting portrait, not only because of its size, but also its unusual composition and play of light and shadows. As I traversed the galleries, I looked at this painting many times – sometimes pausing in front of it for several minutes – but it was only on my fourth day that I really saw it.

On that day, one of the AMBHPE fellowship’s course directors, museum educator Corinne Zimmerman, led a VTS session focused on Sargent’s painting. As described in a previous post, VTS begins with learners taking a silent moment to look closely at the painting, followed by the facilitator posing a series of three questions: “What’s going on in this picture?” “What do you see that makes you say…?” and “What more can we find?” Despite having looked at this painting multiple times over several days, it was only through the close looking and collaborative dialogue facilitated by the structure of the VTS method that I really saw. And what I saw – or rather hadn’t seen previously – amazed me.

The setting for the portrait is the Boit family’s Parisian apartment foyer, in which stand two tall blue and white vases, one against which a girl is leaning. Although I had noticed the vases as part of the painting’s overall composition, I hadn’t looked ‘outside the box’ or, in this case, ‘outside the frame,’ to realize that these same 6-foot tall blue and white vases – decorated with birds and flowers–are also standing in Gallery 232 on either side of Sargent’s painting! I had looked at the painting, but I hadn’t really seen it, at least not in context.

(It turns out that the Boits’ youngest daughter, Julia, who was four at the time Sargent painted her portrait and that of her sisters in 1882, inherited the vases – examples of 19th century Japanese Arita ware – from her parents. Upon Julia’s death, her own daughters then inherited the two vases and, in 1997, Julia’s daughters made them a gift to the Museum.)

From this startling experience – of looking but not seeing the obvious connection between the vases in the painting and the vases in the gallery – I took away at least one lesson relevant to clinical care. Sometimes, when we encounter our patients, we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” Within the “frame” of the exam room, we might look at our patients and listen to their “chief complaints,” without considering these within the settings of their lives– families, communities, work – and so we end up not really seeing or hearing our patients at all.

Going forward, I plan on making more time in my visits with patients, not only to look more closely and listen more fully, but to take a step back and connect what I am seeing and hearing to the broader context of their lives.

Dr. Smyth Zahra

Travelling back to Boston for the second session of our inaugural Fellowship coincided not only with the return of the Swan boats on the lake in the Public Gardens, but also with the MFA’s first exhibition of Frida Kahlo’s work. As we reconnected and immersed ourselves once again for further clinical learning sessions in the art museum, it was interesting to watch so many members of the public come to pay homage to this iconic woman and her work.

Travel, pilgrimage, storytelling, art, religion and clinical practice are all inextricably linked. The Sacra Infermeria, one of the world’s first purpose built hospitals, built in Malta by the Knights of the Order of St John in 1574, provided pilgrims with the very best of available care and still stands today. The Latin word ‘hospes’ meaning foreigner or guest also gave rise to the term hospitality, from which came hospice, hospital, and later, hotel. The relationship therefore, between host and guest, carer and patient was defined and described. Conservation, curation, and care all derive from similar Latin roots and as a restorative dentist I have previously found much in common with the instruments, embodied knowledge, and values of sculptors, conservators, and curators, all of us focusing closely, working with, and caring for the fragile, precious, often irreplaceable.

As long ago as 1897, the philosopher and educational reformer, John Dewey, felt that clinicians were in a unique environment to integrate science and the humanities. “When science and art thus join hands the most commanding motive for human action will be reached, the most genuine springs of human conduct aroused and the best service that human nature is capable of guaranteed,” (Dewey 1897). He later wrote, “If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow.” (Dewey 1944). These words hold true today – taking students and residents out of the usual clinical environments into the art museum space can not only support the transformative learning necessary for their professional development, but also, that integrated arts and humanities based learning may improve not only their observational and communication skills, but more importantly, their ability to care for their patients and themselves.

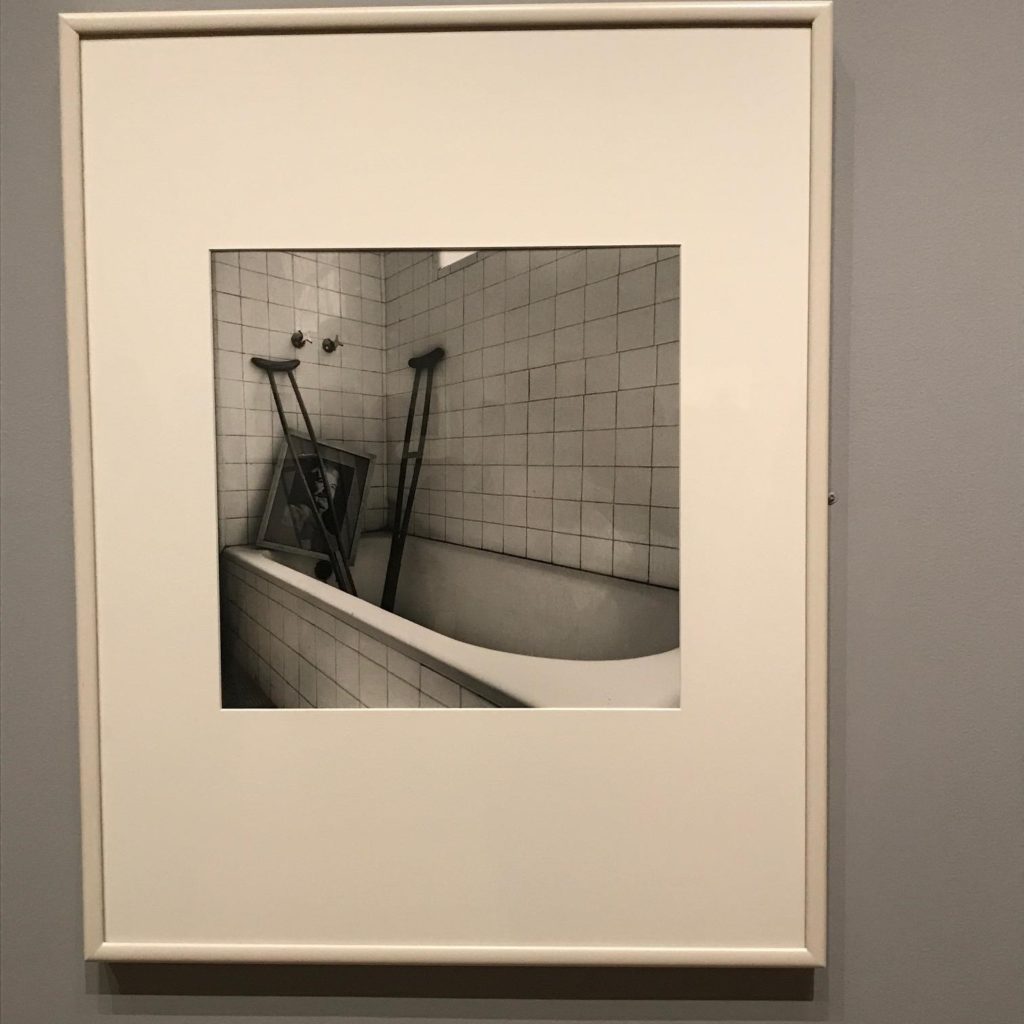

As guests in the gallery space, with sessions delivered jointly by experienced museum curators and clinical educators, there is real opportunity for learning through self-exploration and that, “by making meaning of objects, people in museums are actually developing – and sometimes even changing – meanings and aspects of themselves, their relationships, and the society in which they live’”(Silverman 2010). If our various student groups had been able to join us in the Boston MFA, I would have encouraged them all to spend time in the “Frida Kahlo and Arte Popular” exhibition. They would have learned about a Mexican artist disabled by polio as a child who intended to study medicine before she was tragically involved in a road accident which left her enduring countless surgeries and living with pain for the rest of her life. They would have seen her art – her self-portraits, the magical realism, her dignified depiction of the poor, the votives, and the powerful mix of art and politics. All this, despite her obvious suffering, disturbingly and voyeuristically captured in Graciela Iturbide’s photographs of the prosthetics stored in Frida’s bathroom long after her death.

In an age when we expect our clinicians to deliver highly skilled, person-centred care, and be compassionate leaders, advocates against injustice, inequalities, and inequities, there was much of relevance here for clinical students to explore, reflect upon, and learn from.

“The world’s museums have always been committed to caring for culture. To insure the next age, museums must help foster cultures of caring.” ~ Silverman, 2010

Stay tuned to CLOSLER for our reflections on clinical excellence sparked by looking at art in June.