Takeaway

Paintings, photographs, and poems can foster dialogue about the human experience of illness and allow learners to approach challenging topics in a more comfortable way.

Lifelong learning in clinical excellence | January 2, 2019 | 3 min read

By Tina Zhang, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

Medical education historically has been more focused on genes and molecules than understanding the human being as an individual. There has been a recent push to incorporate more humanities into medical education, as medical schools are beginning the recognize the importance of arts-based curricula in the development of humanistic clinicians. Here at Hopkins, many clinician educators have been trying to improve humanities teaching in medical education. During my first year of fellowship, I joined a project entitled BEAM (Bedside Education in the Art of Medicine), created and spearheaded by Margaret Chisolm, MD, and Susan Lehmann, MD, faculty in the Department of Psychiatry.

BEAM is an innovative arts-based digital resource with the goal of incorporating more humanities in medicine. It is based on Parker Palmer’s pedagogical approach of “third things,” where images or text serve as conversational medicators to create a safe space for sharing perspectives that might be emotionally charged. BEAM uses various “third things,” such as modules of paintings, photographs, or poems, with the hope that they can foster dialogue about the human experience of illness and allow learners to approach challenging topics in a more comfortable way than direct revelation.

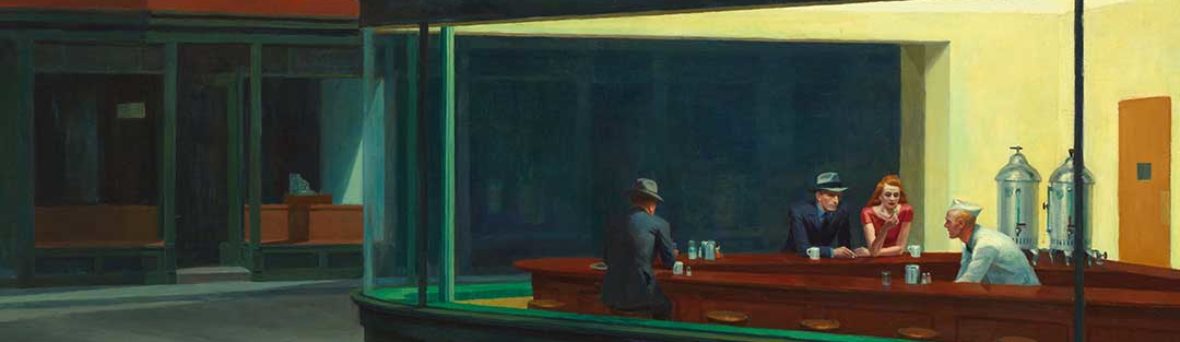

When joining this project initially, I was a bit hesitant and skeptical about whether using a painting could be an effective method for discussing patients. However, I recently used a painting while attending on the inpatient medicine wards. One of the patients on our service was blind and had lived alone for years after his wife passed away. I chose the “Nighthawks” painting by Edward Hopper to discuss this patient and his loneliness with my medical team. What ensued was a rich and fruitful discussion on the importance of thinking beyond immediate tasks and to-dos, and taking a step back and remembering that the patient is more than just another name on the long census list. After discussing the painting and how it related to our patient, my learners individually spent more time with this patient and learned even more about his life outside of the hospital, which allowed for us as a team to facilitate a safe discharge.

Here are some things to remember when thinking about how to incorporate more humanities in medical education:

1.) You don’t have to be a content expert.

My understanding of art is limited to what I learned in art class in high school. I definitely am not a content expert. However, I found that by using a painting with a clear and unambiguous theme, I was able to lead a rich discussion about a patient without knowing any background on the artist or the painting. Similarly, learners with no humanities background can still contribute significantly just through observation alone.

2.) It doesn’t have to take up much time.

Inpatient rotations are busy – rounds take up the majority of the morning, while daily tasks keep teams occupied in the afternoon. However, it is possible to take time out of a busy day – even if it is five or ten minutes – to take a step back as a team and discuss patients on a humanistic level. When time is an issue, it is helpful to choose paintings or poems that present a clear theme to facilitate efficient discussion. More time can then be spent discussing the patient rather than the painting or poem.

3.) Teaching humanities in medicine is important – make it a priority.

Empathy is an important characteristic of a clinically excellent physician, however empathy among medical students has been shown to decline over time. Current literature shows that arts-based teaching has been associated with reduced burnout and increased empathy among medical students. In the current era of medical education, incorporating more humanities and arts-based teaching could encourage the development of more humanistic physicians.

What has your experience been with incorporating humanities in medicine with learners or patients?

We also invite readers to send in any public domain paintings or poems for consideration for BEAM. BEAM is currently undergoing pilot testing. If you’re interested in BEAM, please email me at czhang91@jhmi.edu