Takeaway

The reality of clinical practice can be complex and uncertain and these sessions away from the clinics in and around the art museum space allow students through haptic exploration to become more comfortable with ambiguity.

Lifelong Learning in Clinical Excellence | December 19, 2019 | 5 min read

By Flora Smyth Zahra, MA Clin Ed, DRestDent RCS, FHEA, Kings College London, Margaret Chisolm, MD, Johns Hopkins Medicine

This is the eleventh in a series of monthly reflections by Dr. Flora Smyth Zahra, a dental educator from King’s College London (Twitter @HumanitiesinHPE; Instagram @clinicalhumanitiestoolbox) and Dr. Margaret “Meg” Chisolm (Twitter and Instagram @whole_patients). Drs. Smyth Zahra and Chisolm participated in the inaugural class of the Art Museum-based Health Professions Education (AMHPE) fellowship. Feeling inspired and uplifted by the program, they pledged to spend at least a half-day every month of 2019 looking at art. This is the story of what they did in November.

Dr. Smyth Zahra

This month saw a series of events around “Heads Up! Innovations in Oral Health” exhibition in the Arcade at Bush House; the culmination of the Arts in Dentistry Innovation Programme—an experimental arts-based approach that has brought new perspectives to the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences’ aim to understand disease, enhance health, and restore function.

Artist Sarah Christie and myself ran an object-based haptics exploration session in the gallery space as a public engagement event which attracted King’s students, other artists, academics members of the general public, and tourists passing by on the Strand. Feedback from the event was very positive, provoking many interesting conversations and enjoyment of the creative time. The activity itself is based on a pedagogical rationale I have been working on over the past few years with my own students and lends itself for others to try who are interested in art museum-based education.

The practice of dentistry, in common with surgical specialties, relies on good proprioceptive and haptics skills, trying to make sense of the unseen, learning how much pressure to exert, and navigating uncertainty. Dental students learn the material science of ceramics and the clinical skills of placing ceramic restorations, however, practical sessions working with clay and ceramic objects provide wonderful opportunities to both improve haptic skills and to explore the nature of aesthetic ambiguity. Building on previous work carried out at King’s College London that showed that drawing improved haptic skills, such sessions delivered jointly by ceramic artists and clinicians have been particularly well received by the students who, through observing and creating their own art, can simultaneously utilise their prior clinical experience and (in the absence of there being any clear answer), “draw out their own questions, reflections, insights, perceptions, feelings, judgments and concepts’ through subjectivity and interpretation.” This approach to clinical education and an “appreciation of what is unknown” is something that many within the health professions have called for, arguing that “making students focus obsessively on what is already known rather than what is not yet known reshapes medical training and practice profoundly. […] Uncertainty in medical practice is equated with bad medicine: knowing is good; not knowing dangerous.” However, the reality of clinical practice can be complex and uncertain and these sessions away from the clinics in and around the art museum space allow students through haptic exploration to become more comfortable with ambiguity.

Dr. Chisolm

In November, I traveled to Phoenix, Arizona for the annual meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Although I connected with a lot of wonderful colleagues and enjoyed many terrific meeting sessions (including on one which reported on the AAMC initiative on the Role of Arts and Humanities in Physician Development: From Fun to Fundamental), the highlight of the trip occurred on my own, before the meeting officially started. On that morning, even though it was 90 degrees Farenheit, I took a 30-minute stroll to visit the Phoenix Art Museum. The Museum’s permanent collection includes the sorts of American, Asian, and European works of art that one typically finds, but has a particularly distinguished collection of Latin American and Western American art. But I was most drawn to the temporary installation by Yayoi Kusama: “You Who Are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies.”

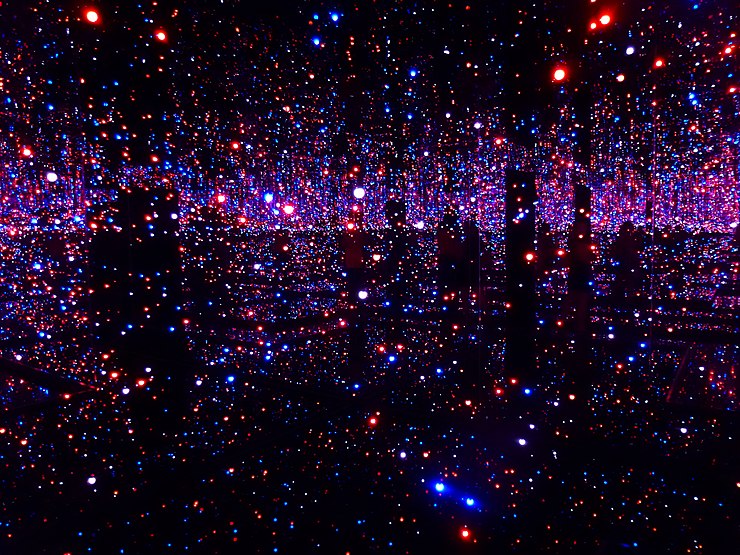

Intrigued? I know I was. Kusama’s “You Who Are Getting Obliterated in the Dancing Swarm of Fireflies” is a dark room completely covered by mirrors. Hung from the ceiling are strands of LED lights, which illuminate in different colors on a loop. After initially feeling disoriented, I next experienced a sense of smallness in the face of an infinite galaxy, as I interpreted the lights as stars. Had I read the information plaque before entering, I would have known that Kusama’s work was inspired by a Japanese fairy tale about a person in a field with 10,000 fireflies, but the intended effect is the same.

Kusama is considered as one of the most important living artists to come out of Japan, and has created installations in various museums around the world, in addition to being active in painting, fashion design, and literature. She is an artist of particular interest to me, as a psychiatrist, because when she was 10 years old, Kusama started experiencing visual hallucinations of flashes of light and fields of dots and flowers. In her 40s, Kusama checked herself into a psychiatric hospital in Japan, where she took up permanent residence (her studio is located nearby). (She is often quoted as saying: “If it were not for art, I would have killed myself a long time ago.”) Despite her psychiatric illness, she has been able to flourish as an artist, producing most recently brightly colored acrylic paintings, as well as writing several published novels, a poetry collection, and an autobiography.

Dr. Tyler Vanderweele—the John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Epidemiology at Harvard University—has written extensively about the concept of flourishing, which is of relevance not only to patients, but also to clinicians. Vanderweele writes:

“Within psychiatry, questions of flourishing may also be central to patient care. Interest has expanded in ‘positive psychiatry’ to promote positive mental health outcomes as well as psychological characteristics and activities that boost resilience to mental disorders….Considerations of flourishing are furthermore personally relevant for clinicians as well, especially given current attention to high physician burnout rates. Greater attention to flourishing for clinicians could bring a heightened sense of meaning, control, and optimism that might help protect against professional dissatisfaction.”

Creating art has clearly helped Kusama flourish despite her psychiatric illness. And beholding Kusama’s art has helped me—and has the potential to help many other clinicians—flourish as well.